Tilda Swinton is the voice of water in a toilet bowl. Emma Stone plays an earnest extra in a low-budget porno. Paul Dano stars as a sitcom dad having an affair with a fluffy purple alien. Ryan Gosling embodies a man driven to insanity by the Papyrus font of the Avatar logo. Steve Buscemiis the letter Q. If anyone can get a big-name star to do something weird for the camera, it’s Julio Torres.

In his capacity as an actor-writer-director, Torres, who is 38 and grew up in El Salvador, has welcomed many a star into his Julio-verse, casting them in his surreal skits on Saturday Night Live and in his leftfield TV shows Los Espookys and Fantasmas. But actors aren’t the only ones taken with his fantastical worlds, most of which exist somewhere at the intersection of Williamsburg and a fever dream; one TV critic called Torres “a beacon of hope for TV’s future”.

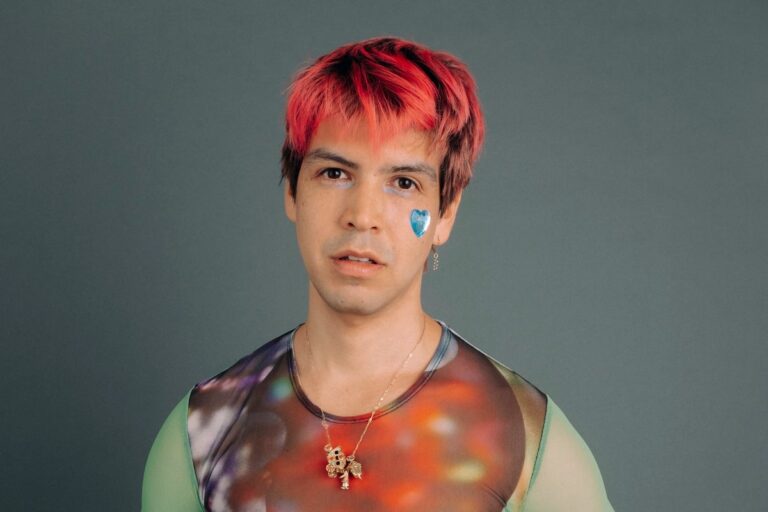

The man I meet for lunch is more low-key than such a grand proclamation might suggest. He’s quick to laugh and chilled out, wearing a shirt printed with the kind of fanciful scene you might find in one of his shows: penguins eating ice cream outside a neo-Classical building. Around his neck is a robot pendant. His hair is spiky, and over the years has functioned like an emotional thermometer: blond, black, blue, platinum. Currently, it’s a shade of red that’s hard to pin down.

Like his hair, Torres’s work tends to evade description: stories so strange and slippery that words slide right off them with nothing to grab onto. It’s why, when describing his new play, Color Theories at Soho Theatre, he can only smile and say: “It’s a show about colours. Dot. Dot. Dot.” The dot-dot-dot is key; Torres practically lives in the dot-dot-dot. More accurately, it’s a one-man show about understanding the world through colours: Dwayne Johnson, for example, is yellow because he’s halfway between a beachball and a gun; Ellen DeGeneres wants to be yellow, but she’s red. As for Torres, right now he’s feeling purple: “Purple is a combination of blue, which is logical, and red, which is passion and anger,” he says. “I feel very red in logical settings.”

Color Theories is a spiritual precursor to My Favorite Shapes, his anthropomorphic HBO comedy special from 2019. In that, Torres wears a futuristic silver suit and sits in front of a pedal-powered conveyor belt carrying everyday objects, which he presents and comments on: a glass pot, a piece of chocolate, a blob-like figurine with googly eyes. It’s like watching the shopping channel from another dimension, one in which the transfer of souls between plastic seahorses is a normal occurrence. If it sounds silly, that’s because it is – ticklingly so – but it’s also emotional, and vaguely philosophical.

As I said, his work defies explanation. Hollywood, by comparison, is an industry practically built on three- or four-word elevator pitches (Ghostbusters with women; Social Network about Uber; Goodfellas for bankers). Torres rolls his eyes. “When I started having meetings with executives, the show they kept bringing up was Broad City,” he says, tucking into a quinoa salad. “They wanted a Latino Broad City, a queer Broad City. The irony being that I am sure most of those people passed on Broad City… is the lesson there not ‘Let’s believe in new, fresh voices’?”

How Torres gets anything greenlit is anybody’s guess. He laughs recalling the pitch meeting for Los Espookys, the two-season Spanish-language series he co-produced with Fred Armisen, which is ostensibly about a group of horror enthusiasts who are paid to stage eerie scenes for money. It’s also about the heir to a chocolatier fortune living with a water demon trapped inside him. Did I mention the water demon is obsessed with the 2010 Colin Firth film The King’s Speech? Try explaining that to a room full of suits.

His ever-growing Rolodex of famous friends helps. “I find that, regardless of how big or celebrated people are in their careers, if you create an interesting world, people will come and want to be part of it,” he says. Buscemi took all of 30 minutes to say yes to Fantasmas after reading the script. Equally, Torres says, “I’ve been very lucky to find champions in these big institutions – very fortunate to always be allowed to play over there.” As his star rises, he hopes to be able to do the same for his peers, and so here, a quick shout-out to Spike Einbinder and River L Ramirez.

Torres grew up in El Salvador, the son of an architect and a civil engineer. His bedroom was lined with shelves that housed all his toys. “They were organised as if it was a museum,” he smiles. “Action figures, Barbies, little cars.” Torres wasn’t into popular culture so much as creating his own. “I’d cast the toys as my actors and create little stories,” he says. Unsatisfied with the Barbie Dream Houses for sale, he asked his architect mother to make a custom penthouse for his dolls, with circular windows and doors that opened irregularly. “I was always the kid who had the poorly executed big idea,” he says, “and I’d so much rather be that [than coming up with small ideas].”

It feels obvious to connect his country’s love of magical realism with the surreal work he makes today. “I didn’t think it had influenced me, but clearly it has,” he admits. “Not in a conscious way, but that absurd and abstracted way of seeing life definitely rubbed off.” On influences, Torres isn’t certain he has any. He adored Late Night with Conan O’Brien, but in the way that an accountant might adore it. “The kind of sketches I grew up loving on SNL [character work with Maya Rudolph and Kristen Wiig], I haven’t created anything like that,” he says.

If there’s a throughline in his work, it’s his distaste for bureaucratic systems. “Something that keeps coming back is the friction or tension between the individual and the systems that rule our lives – how isolating that can be,” he says. “And absurd.” In Problemista, his directorial debut for A24, he plays a version of himself – a toy designer from El Salvador who loses his job and must find a sponsor to stay in the US. Tilda Swinton plays the manic, flame-haired art dealer who takes him on as her assistant; Isabella Rossellini narrates.

It’s a funny take on a deadening experience, I suggest. “I think that’s just my nature,” he says. “I metabolise things through humour a lot, so it’s not me trying to do something. That’s just how it is. I don’t know if it would be different if something truly, deeply, horribly traumatic would have happened to me, but for now, that’s how I see the world.”

Like his character, Torres also went through visa hell. After graduating from university, he was given one panic-filled year to secure a work visa. Eventually, he landed a job in the art world. All the while, he was making and sharing hilarious, and often strange, videos with his roommate Einbinder. The pair amassed a cult following in the real world, too, performing at bars and comedy clubs. When in 2015 Torres’s visa was up, and he had to pay more than $5,000 in legal and filing fees, his new friends in the comedy world made a video called Legalize Julio and raised the money in an hour. Torres’s new visa classified him as an “alien of extraordinary ability”.

He doubled down on the alien motif with last year’s Fantasmas. The series, essentially six hours of stitched-together vignettes, is loosely held together by the narrative of his character (also called Julio) as he sets about getting a Proof of Existence card in order to sign the lease on a new apartment – or do pretty much anything. On his journey, he is blocked at every turn, trapped in a labryinth of pencil-pushers, systems and corporations, all seen through Torres’s singular, meandering filter. At one point, Bowen Yang appears as an elf taking Santa to court for wages. How we get there is beside the point.

I don’t want to provide a symbolic gesture of obedience

The fictional Proof of Existence isn’t so fictional. It’s not dissimilar to a credit score, Torres tells me. “Miss a payment? Your score goes down,” he says. “However, choosing not to play the game and choosing never to have a credit card, never to take out a loan, never to spend money you don’t have, gives you a bad credit score. Abstaining from the game gives you bad credit.” To this day, he’s never had a credit card. “I don’t want to provide a symbolic gesture of obedience,” says Torres. His capitalist abstinence can make life trickier – “but it’s worth it!”

With all the fanfare and the famous co-signs (Gosling reached out to Torres to do Papyrus 2), Torres is becoming hot property himself. He has, though, little interest in the indie-to-blockbuster pipeline: “I don’t think it would be a good use of me.” There is one character that could entice him into the franchise-verse. “Calendar Girl,” says Torres, referencing the incredibly obscure Batman villain. “Calendar Girl is a former model who got really bad plastic surgery so she covers her face, and she’s out for vengeance on brands and agents and magazine editors.” He sounds giddy on the idea. “If anyone wants to make a Calendar Girl movie, let me know.”

‘Color Theories’ is on at Soho Theatre until 16 August; tickets here