With a population of just over 2,000, Ulefoss might not seem like the answer to one of Europe’s current economic problems. But this dot on the southern Norwegian landscape happens to perch directly above the continent’s largest deposit of rare earth elements.

These hard-to-acquire metals are crucial components of many modern technologies and appliances, from fighter jets to electric vehicles, flat-screen TVs to digital cameras.

They’re so important, in fact, that having a secure supply of them has become a part of European Union law. Because, right now, the EU has no internal supply of its own, Ulefoss holds promise.

The hidden deposit known as the Fen complex slumbers as close to the surface as 100 meters (328 feet). It sits right below the community’s schools and homes, making it a tricky and potentially controversial operation for the Rare Earths Norway (REN) mining company.

One resident who asked not to be named said three of the sites the municipal council is exploring as landfills for the mines are currently ponds.

“For me, existing ponds are nearly holy considering the climate problems we have or will be having. Had this been in the 1950s when I was a boy, I could understand it, but when the plans are for 2025, I react very strongly against it.”

But Tor Espen Simonsen, REN’s community liaison and a local himself, says the company has worked hard to address the villagers’ concerns.

“Many people are curious towards new mining activity, hoping that this will bring back jobs and bring people,” he said. “And we are working very closely with local businesses to strengthen value creation locally.”

So far at least, the project has avoided drawing the kind of protests and local government objections that often hamper similar large infrastructure initiatives. The town’s past lends itself to this support.

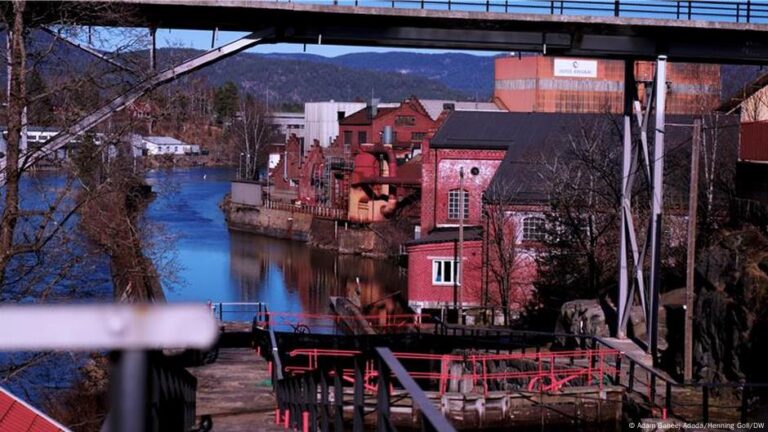

Mining is a known quantity for Ulefoss

Ulefoss is one of Europe’s oldest industrial communities, with a history of iron mining dating back to the 1600s. The last pit shut down in the 1960s, as smaller operations in Norway lost ground to the forces of globalization and international trade.

“Growing up in Ulefoss, many people have said that one day there will be new mining activity,” Simonsen said. “We just don’t know when.”

But if REN’s project proceeds as planned, that day might not be too far off and could become the community’s most significant chapter of mining activity. The company says it has identified 9 million tons of rare earth oxides, which puts the deposit on a similar scale to the world’s largest active mines in China and the United States.

The company hopes to begin full-scale operations in 2030, but it can only extract these rare earth elements if it can do so without affecting or displacing the village above.

To do this, REN is planning to create what it calls an “invisible mine.” Starting about 4 kilometers away from the town center, it will dig a long, narrow diagonal tunnel directly into the heart of the Fen deposit. Using automated drills, it will then dig out giant, 300-meter-by-50-meter sections of the deposit.

That material will be dropped into a crusher directly below the point of excavation. Once pulverized, that will be sent back to the surface on conveyor belts to be separated at the processing site, which will be built near the entrance to the tunnel.

How will the underground mining impact the village?

The risk with this approach is subsidence. The newly created empty space below ground could cause geological instability, as was the case in Sweden’s most northerly town, Kiruna.

The Kiruna iron ore mine has left the urban center above it with cracks and ground deformation. So in the early 2000s, it was decided the town would need to permanently relocate, a process that is currently underway. That experience hasn’t gone unnoticed in Ulefoss.

“There are some people who have seen things from other places. They’re scared that our houses will fall in a big crater, or that something will be destroyed,” said local resident Eli Landsdal. “But I feel now we have come to a place where more and more people are moving from the negative side to the positive side.”

To avoid the same fate as Kiruna, REN plans to return around half of its waste material back to the holes left in the Fen deposit, mixed with a binding agent to strengthen the rock.

The invisible mine could become a gamechanger for Europe

If the company manages to pull off its ambitions, it would be a coup for the EU as it currently rushes to secure an internal supply of the critical materials also used for renewable energy, aerospace and defense, which, for the most part, are currently sourced fromChina .

The supply chains are also firmly under Chinese control, which leaves the EU at the mercy of whatever geopolitical tensions and shifts the future holds. This came into sharp relief in April when Beijing imposed export controls on rare earth elements and magnets.

Though Norway is not a part of the EU, it is a close ally with strong trading ties, and the nascent European rare earth supply chain would be the main target for whatever comes out of Fen.

“We are far behind, both in the EU and of course in Norway,” said Tomas Norvoll, the state secretary of Norway’s Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, which is responsible for the mining sector. He highlights the importance of not to getting “locked out” of magnet supply chains. “Therefore it is important that we do it with our own resources here.”

Fen’s new mine is still decades away from the company’s dream of supplying a third of Europe’s estimated demand for rare earth elements. But the company hopes to start a small-scale pilot operation next year. If all goes to plan, that would become the first industrial source of rare earth elements in Europe.

Edited by: Tamsin Walker