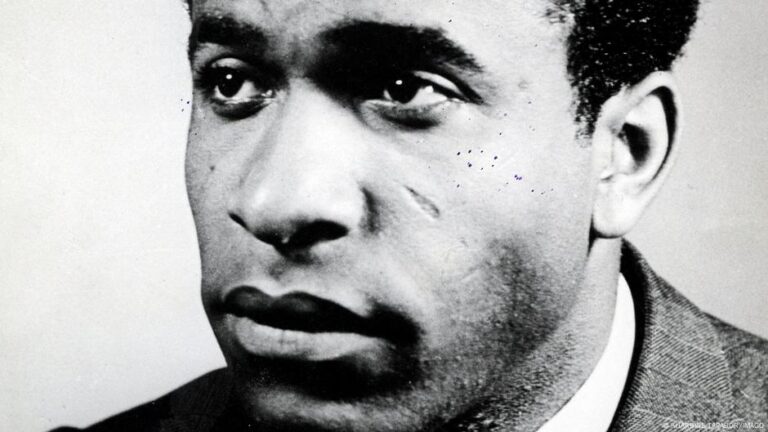

Fanon is regarded as a crucial figure of early anti-colonial and anti-racist theory. For Algerians, he is one of the heroes of the country’s struggle for independence.

Yet his role during the war against France and his writings remain largely unknown to a wider public.

July 20, 2025, marks the 100th anniversary of his birth. Fanon was not granted a long life: At just 36, he died of leukemia in 1961 without ever witnessing Algerianindependence, a goal he devoted his life to.

Fight for African unity

His work is “a reflection on the concept of solidarity, understanding what solidarity means in a moment of war, of resistance,” Mireille Fanon Mendès France told DW. She is Fanon’s eldest daughter and co-chair of the international Frantz Fanon Foundation.

She says she barely knew her father and retains few childhood memories of him, but as a teenager, she immersed herself in her father’s literary work.

Fanon’s writings made it clear that the struggle for Algerian independence not only benefited Algeria, but was also about African unity. “And this African unity is still not there,” his daughter explains.

In her Paris apartment, Alice Cherki goes through old documents from her youth during Algeria’s war of independence against France: “I knew then that it was colonialism,” she recalls. Now 89, she knew Frantz Fanon well. She worked alongside him in the 1950s as an intern at the psychiatric clinic in Blida, Algeria.

Frantz Fanon was the head of the psychiatric department and not only cared for the sick but also helped Algerian nationalists. “We took in the wounded, the fighters who came here,” Cherki said. Fanon set up a supposed day clinic within the hospital, only for show. In reality, he secretly took in the wounded and those who needed to recover, Cherki told DW.

Commitment to the “Algerian cause”

Born in the French colony of Martinique, Fanon grew up in a French colonial society and was deeply influenced by his experiences: He volunteered for World War Two for France at the age of 17. As a Black man though, he experienced daily racism in the French army. After the war, he studied medicine and philosophy in France and later moved with his wife Josie to Blida in French-Algeria, where he became chief physician of the psychiatric clinic.

From the beginning of the war in 1954, Frantz Fanon was helping Algerian nationalists while continuing to work as a psychiatrist. He established contacts with several officers of the National Liberation Army as well as with the political leadership of the National Liberation Front (FLN), especially its influential members Abane Ramdane and Benyoucef Benkhedda. From 1956 on, he was fully committed to the “Algerian cause.”

Amzat Boukari Yabara is a historian and author of the 2014 book “Africa Unite,” which traces the history of Pan-Africanism. He emphasizes the significance of Fanon’s resignation from his position as a doctor in the fall of 1956.

“By this time, he had already made contact with several FLN members and would later go to Tunis, where an FLN branch was established,” explains Yabara. “From Tunis, he participated in the struggle by writing for the FLN newspaper El Moudjahid under a pseudonym.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, he became ambassador of the provisional government of the Algerian Republic – the government-in-exile of the FLN – in Accra, a traveling ambassador for sub-Saharan Africa.”

Crucial works of anti-colonial theory

Frantz Fanon wrote some of the most influential texts of the anti-colonial movement, like his early work “Black skin, white masks” about the psychological effects of racismand colonialism on Black people.

His most important book though was “The Wretched of the Earth” where he focuses on revolutionary action and national liberation.

The book was published with a foreword by Jean-Paul Sartre shortly before his death in 1961.

On July 5, 1962, Algeria gained independence after an eight-year armed struggle against the then-colonial power, France. Historians estimate the number of Algerian deaths at 500,000; according to the French Ministry of the Armed Forces, approximately 25,000 soldiers lost their lives.

Keeping the memory alive

Anissa Boumediene is a writer, lawyer, and former First Lady of Algeria. She was the wife of President Houari Boumediene, who ruled the country from 1965 to 1978. “Frantz Fanon is part of Algerian history. He defended independence. He was truly an infinitely respectable person,” she told DW.

But even in Algeria, 64 years after his death, his memory should not be taken for granted, says journalist Lazhari Labter, who translated Fanon’s writings into Algerian Arabic.

“Today’s generations have become increasingly ignorant of the history of their country, and especially of this subject,” he explains. “And of course, apart from very small circles, apart from universities and intellectuals, the name Fanon doesn’t mean much to younger generations. This may be because his works are not taught in schools, high schools, or universities.”

Two new films – “Fanon” by Jean-Claude Barny, released in April 2025, and “Frantz Fanon” by Algerian director Abdenour Zahzah, released in 2024 – are intended to keep his memory and his anti-colonial theories alive.

This article was originally published in German.