A dictator wearing reflective sunglasses, medals arrayed across his chest; a parliament in disarray; a people silenced by impunity.

These are images we may envision when we hear the phrase “banana republic.”

The term was coined by US writer O. Henry (real name: William Sydney Porter), who’d fled to Honduras in 1896 to escape embezzlement charges by a Texas bank.

In the coastal city of Trujillo, he’d observed how the US-owned United Fruit Company dominated the city’s railways and docks and wielded significant political influence. This inspired his novel “Cabbages and Kings” (1904), in which he wrote about the fictional republic of Anchuria — a “small, maritime banana republic” whose government bent to the interests of a powerful foreign corporation.

“Since then, it has been loosely used by US scholars, journalists, politicians and writers as a synonym of a corrupt, failed state,” said Carlos Dada, co-founder and director of the Salvadoran digital news outlet, El Faro.

Not just a fruit company

Dada, who has covered investigative stories on power, corruption and criminality in Central America, explains that the original “banana republics” were four Central American countries — Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Costa Rica — where US banana companies, United Fruit Company (UFC) and Standard Fruit (now known as Chiquita and Dole respectively), controlled much of the land and political life.

With Washington’s support, these firms helped install loyal governments and pressured or removed leaders who resisted their terms.

“Banana republics are arguably the closest the United States ever was to a colonizing power, without the demands and responsibilities that colonizers had over the colonized elsewhere,” Dada wrote in an essay on the topic sent to DW.

An infamous example happened in Guatemala after its democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz, attempted to redistribute unused plantation land. The move threatened the holdings of the UFC, which at one point controlled vast tracts of Guatemala’s arable land.

In June 1954, Arbenz was deposed in a CIA-sponsored coup to protect the fruit company’s profits, and Arbenz was replaced by a brutal US-backed regime that committed widespread human rights abuses.

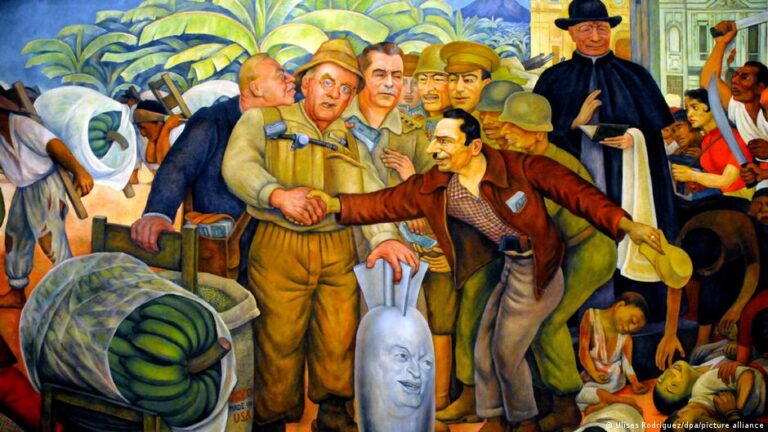

Mexican muralist Diego Rivera (husband of Frida Kahlo) documented the event in “Glorious Victory,” portraying the United Fruit Company, the CIA and US officials as central actors in Arbenz’s downfall.

Colonial violence, then and now

The banana republic system exacted a human toll, too.

Labor disputes on banana plantations often ended in violence. One notorious episode is the 1928 Banana Massacre in Colombia, where the army fired at striking UFC workers for demanding better wages and work conditions; women and children were among the victims. Nobel literature laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez later wove a version of it into his 1967 novel, “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

American historian and author Aviva Chomsky argues that colonial violence is as much part of the present as it is of the past, drawing comparisons with recent events in Gaza, Venezuela or Minneapolis.

“And accusing the victims of being violent, dangerous, threats to national security, terrorists in need of a strong hand of military repression to keep them under control — we are still reading that in the news every day,” she told DW.

The US: A banana republic?

The term “banana republic” also peppered US political commentary after the January 6 Capitol riot in 2021. Chomsky argues this framing “looks at the results, rather than the causes.”

She described the US as “inherently” a banana republic because the extractive banana‑company model “is as much a foundational source of US history as it is of Honduran history.”

The United States’ vast overconsumption is “a result of our colonization of everything from land to the atmospheric commons. Which is to say — bananas, or colonial extractivism, made the US what it is today.”

Chomsky also points to the US’s long history of backing coups across Latin America and in other parts of the world. She illustrates this with a joke that circulated in Latin America after the January 6 riots: “Why is there never a coup in the US? Because there is no US embassy there.”

Pejorative or descriptive?

American scholar and linguist Anne Curzan notes that “banana republic” has undergone a semantic drift typical of living languages.

While it originally referred to the history above, “over time, the term came to be associated with other characteristics of some of these nations — which, it is important to remember, were often being exploited by these foreign corporations — including instability, military rule and/or a dictator, and sometimes corruption,” she told DW.

Today it is also applied to countries with no such corporate or commodity‑export history. Curzan adds that this widened use has created ambiguity around the term.

“It is typically a pejorative term — that is less ambiguous. But it’s worth taking the time to be sure we’re clear on what we or others are trying to critique with the term ‘banana republic,'” she added.

Chomsky picked up this point.

“If it refers to some inherent characteristic of the people, then it’s racist and derogatory,” she said. “If it refers to historical relationships that have undermined sovereignty, then it’s a useful term.”

This distinction matters, she argues, because there is a tendency to treat poverty, violence and corruption as if they were inherent to Central America. She points to how President Joe Biden once attempted to address the “root causes” of migration, poverty, violence and corruption. Had he asked what those root causes were, Chomsky argued, “he would have had to confront the ways that his very ‘solutions’ — US military control, aid and investment — were what caused those problems to begin with.”

“Banana republic” has since entered other languages, including German, French or Spanish. Chomsky says it is also used in Latin America in political or academic contexts. She says most Latin Americans are less concerned if the term is politically correct; it takes away focus from ugly realities.

“We have to be able to talk about the historical relationships that have undermined sovereignty, not pretend that every country is just a free‑floating billiard ball rolling around on a pool table on equal terms.”

Edited by: Elizabeth Grenier