The Trump administration took steps on Monday that appear likely to result in new tariffs on semiconductors and pharmaceutical products, adding to the levies President Trump has put on imports globally.

Federal notices put online Monday afternoon said the administration had initiated national security investigations into imports of chips and pharmaceuticals. Mr. Trump has suggested that those investigations could result in tariffs.

The investigations will also cover the machinery used to make semiconductors, products that contain chips and pharmaceutical ingredients.

In a statement confirming the move, Kush Desai, a White House spokesman, said the president “has long been clear about the importance of reshoring manufacturing that is critical to our country’s national and economic security.”

The new semiconductor and pharmaceutical tariffs would be issued under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which allows the president to impose tariffs to protect U.S. national security.

Earlier in the day, Mr. Trump hinted that he would soon impose new tariffs on semiconductors and pharmaceuticals, as he looked to shore up more domestic production.

“The higher the tariff, the faster they come in,” Mr. Trump told reporters at a White House appearance, citing import taxes he has imposed on steel, aluminum and cars.

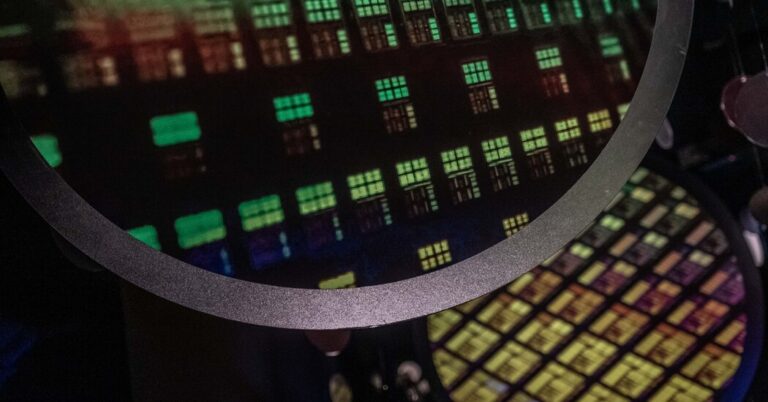

Semiconductors are used to power electronics, cars, toys and other goods. The United States is heavily dependent on chips imported from Taiwan and elsewhere in Asia, a reliance that Democrats and Republicans alike have described as a major risk to national security.

As for pharmaceuticals, Mr. Trump argued that too many vital medicines were imported. “We don’t make our own drugs anymore,” he said.

Some drugs are produced at least in part in the United States, though China, Ireland and India are significant sources of some types of pharmaceuticals.

Mr. Trump also signaled Monday that he could offer certain companies relief from his tariffs, as he did for electronics imports in recent days — a break from his past insistence that he would not spare entire industries.

The president said he was “looking at something to help some of the car companies, where they’re switching to parts that were made in Canada, Mexico and other places.” He added, “And they need a little bit of time because they’ve got to make them here.” Shares of General Motors, Ford Motor and Stellantis jumped after his comments.

“I’m a very flexible person. I don’t change my mind, but I’m flexible,” Mr. Trump said on Monday when asked about possible exemptions. He added that he had spoken to Apple’s chief executive, Tim Cook, and “helped” him recently.

The president has announced significant changes over the last week to his trade agenda, which has roiled markets and spooked the businesses that he is trying to persuade to invest in the United States.

Mr. Trump announced a program of global, “reciprocal” tariffs on April 2, including high levies on countries that make many electronics, like Vietnam. But after turmoil in the bond market, he paused those global tariffs for 90 days so his government could carry out trade negotiations with other countries.

Those import taxes came in addition to other tariffs Mr. Trump has put on a variety of sectors and countries, including a 10 percent tariff on all U.S. imports; a 25 percent tariff on steel, aluminum and cars; and a 25 percent tariff on many goods from Canada and Mexico. Altogether, the moves have increased U.S. tariffs to levels not seen in over a century.

Amid a spat with China, Mr. Trump raised tariffs on Chinese imports last week to an eye-watering minimum of 145 percent, before exempting smartphones, laptops, TVs and other electronics on Friday. Those goods make up about a quarter of U.S. imports from China.

The administration argued that the move was simply a “clarification,” saying those electronics would be included within the scope of the national security investigation on chips.

But industry executives and analysts have questioned whether the administration’s real motivation might have been to avoid a backlash tied to a sharp increase in prices for many consumer electronics — or to help tech companies, like Apple, that have reached out to the White House in recent days to argue that the tariffs would harm them.

Mr. Trump has already used the legal authority under Section 232 to issue tariffs on imported steel, aluminum and automobiles. The administration is also using the authority to carry out investigations into imports of lumber and copper.

The notices on Monday said the administration had begun its investigations into imports of pharmaceuticals and semiconductors on April 1. Neither the White House nor the president previously said the process had officially begun.

Kevin Hassett, the director of the White House National Economic Council, told reporters on Monday that the chip tariffs were needed for national security.

“The example I like to use is, if you have a cannon but you’re getting the cannonballs from an adversary, then if there were to be some kind of action, then you might run out of cannonballs,” he said. “And so you can put a tariff on the cannonballs.”

Mr. Trump has argued that tariffs on chips will force companies to relocate their factories to the United States.

Some tech companies have been responsive to the president’s requests to build more in the United States. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, the world’s largest chip manufacturer, announced at the White House in March that it would spend $100 billion in the United States over the next four years to expand its production capacity.

Apple has announced that it will spend $500 billion in the United States over the next four years to expand facilities around the country.

On Monday, Nvidia, the chipmaker, announced that it would produce supercomputers for artificial intelligence made entirely in the United States. In the next four years, the company said, it will produce up to $500 billion of A.I. infrastructure in the United States in partnership with TSMC and other companies.

“The engines of the world’s A.I. infrastructure are being built in the United States for the first time,” Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s chief executive, said in a statement.

The White House blasted out the news in an announcement that credited the president.

“It’s the Trump Effect in action,” the statement said, adding, “Onshoring these industries is good for the American worker, good for the American economy and good for American national security — and the best is yet to come.”

But some critics have questioned how much tariffs will really help to bolster the U.S. industry, given that the Trump administration is also threatening to pull back on grants given to chip factories by the Biden administration. And foreign governments like China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan all subsidize semiconductor manufacturing heavily with tools like grants and tax breaks.

Globally, 105 new chip factories, or fabs, are set to come online through 2028, according to data compiled by SEMI, an association of global semiconductor suppliers. Fifteen of those are planned for the United States, while the bulk are in Asia.

Mr. Trump has criticized the CHIPS Act, a $50 billion program established under the Biden administration and aimed at offering incentives for chip manufacturing in the United States. He has called the grants a waste of money and insisted that tariffs alone are enough to encourage domestic chip production.

Jimmy Goodrich, a senior adviser to the RAND Corporation for technology analysis, said tariffs could be effective “if used smartly, as part of a broader strategy to revitalize American chip making that includes domestic manufacturing and chip purchase preferential tax credits, along with clever ways to limit the coming tsunami of Chinese chip oversupply.”

“However,” he added, “the United States on its own only accounts for about a quarter of all global demand for goods with chips in them, so working with allied nations is critical.”

Administration officials have suggested that chip tariffs could be applied to semiconductors that come into the United States within other devices. Most chips are not directly imported — rather, they are assembled into electronics, toys and auto parts in Asia or Mexico before being shipped into the United States.

The United States has no system to apply tariffs to chips encased within other products, but the Office of the United States Trade Representative began looking into this question during the Biden administration. Chip industry executives say such a system would be difficult to establish, but possible.

Rebecca Robbins contributed reporting from Seattle.