Within seconds of meeting Sean Hayes, I realise I’ve fallen prey to a classic trap. The actor is known for playing Jack, the gloriously camp best friend in the hit sitcom Will & Grace: a spritely Peter Pan figure so melodramatic that he gets into a Cher-off with the real Cher and wins. One of the most memorable comic creations of the Noughties, Jack is hard to shake. And so, when Hayes walks – not bounds, not skips, not somersaults – into the dimly lit bar of the Barbican, it takes a minute for me to recalibrate my expectations.

I’m not the only one. Audiences are having to rethink their perception of the actor, now 55, in light of his Tony-winning turn on Broadway as the troubled pianist-raconteur Oscar Levant, who died in 1972. Three years after its American debut, Good Night, Oscar is transferring to London with Hayes stepping back behind the keys and into Levant’s shiny black wingtips. That one-year break was necessary: “They had asked me about transferring towards the end of the New York run,” he recalls, reclining in his chair. “They said, ‘Do you want to go to London?’” He raises his eyebrows past his thick black frames. “And I said, ‘No, I want to go to bed.’”

Playing Levant is demanding. The pianist was as famous for films like An American in Paris as he was for his volatile TV appearances that showed off his wicked wit and far-ranging intellect. His struggles with mental health and addiction to prescription drugs were not obstacles to his charm but fodder for it. On air in front of millions, Levant would crack jokes about his fragile mental state. Asked what he did for exercise, he responded: “I stumble and then I fall into a coma.”

As roles go, Levant is an actor’s dream: a real meaty character with a network of sinews and tendons, layers of flesh to tear into. It’s the hard stuff. “Nobody would have ever cast me in this role,” Hayes admits. That he landed the part was the result of 20 years of hard work campaigning for himself, together with the production’s team. “When you’re an actor like I am, you have to create your own path,” he says. “You have to become self-generating because nobody’s going to do the work to see you in other roles. They’d rather just check boxes, which I get.” He’s forgiving of the industry’s blinker vision: “If I were in the same position, I’d probably do the same thing.”

That said, it has been satisfying for Hayes to show off the other tools in his kit, not least his skills as a classically trained pianist. He began lessons at age five; his teacher was his neighbour. By his teens, he was performing Mozart in competitions, and later, at college, he was hired as the music director of a dinner theatre. In a virtuoso final scene of Good Night, Oscar, he puts this lesser-known gift to spectacular use with a fast-fingered rendition of “Rhapsody in Blue”.

Though it’s taken a while to reach this point, Hayes has long made peace with the slow burn of his career. “Had this come to fruition earlier,” he says, “I don’t know that I would have been ready to avail myself to an audience in the way that I do with this. It kind of happened when I stopped giving a s***.” He rushes to clarify: “By that I mean, not giving a s*** as in embracing the fear of expressing myself.” He needn’t have clarified; if anything is clear from his performance, underpinned by a careful study of Levant’s tics and mannerisms, it’s that Hayes cares. A lot.

In a sense, he has been waiting for this since Will & Grace initially came to an end in 2006. The groundbreaking NBC sitcom helped normalise gay characters in the 1990s and in doing so, made stars of its cast. As for the criticism that Jack’s character, ebullient and loud, perpetuated gay stereotypes, Hayes says he tuned it out. “I never thought deeper than I’m an actor who needs to act,” he says. “And I didn’t want to think deeper than that. We educated America without them knowing it, and we did it through comedy.”

What comes next is an age-old tale: actor gets famous doing one thing and is tied to it forever. “Once you’re on a hit show like that, you know it’s going to be tough,” he says now. “I loved it and I love the people, but even when I was in it, I was like, ‘OK what’s the plan to get out of this?’ And so, I would go to meetings and this and that, but I wasn’t ready. I am now but it might be too late, and that’s OK too.” Ready for what? Hayes pauses a moment. “To take on new challenges in a way that I was never open to before.”

-2--Credit-Johan-Persson.jpg)

In person, dressed in a zip-up sweater and jeans, Hayes is to the point and affable. He speaks efficiently like a doctor with back-to-back patients, every sentence packed with the maximum information in the fewest words possible. On where his impulse to perform comes from, a question that typically tugs spools of thought from actors, Hayes reels off his reasons in rapid fire: “Youngest of five; needing attention; no dad; somebody love me!” He smiles. “I think it’s the same with any performer and if they tell you anything different, they’re lying.”

He grew up poor in Chicago, Illinois, and frequently went without school lunches, his mother struggling to make ends meet for Hayes and his four siblings after his dad left when he was five years old. “We went through winter with no heat. Our phone was always turned off because we couldn’t pay the bill. The car was repossessed. Sometimes we had no food.” The tough times, Hayes adds, were blessings in disguise. “Watching my mum work so hard and growing up like that gives you this incredible work ethic that all five of us have inherited. All five of us work really hard and I love that.” (Hayes spent his first big pay cheque on a piano for $6,000.)

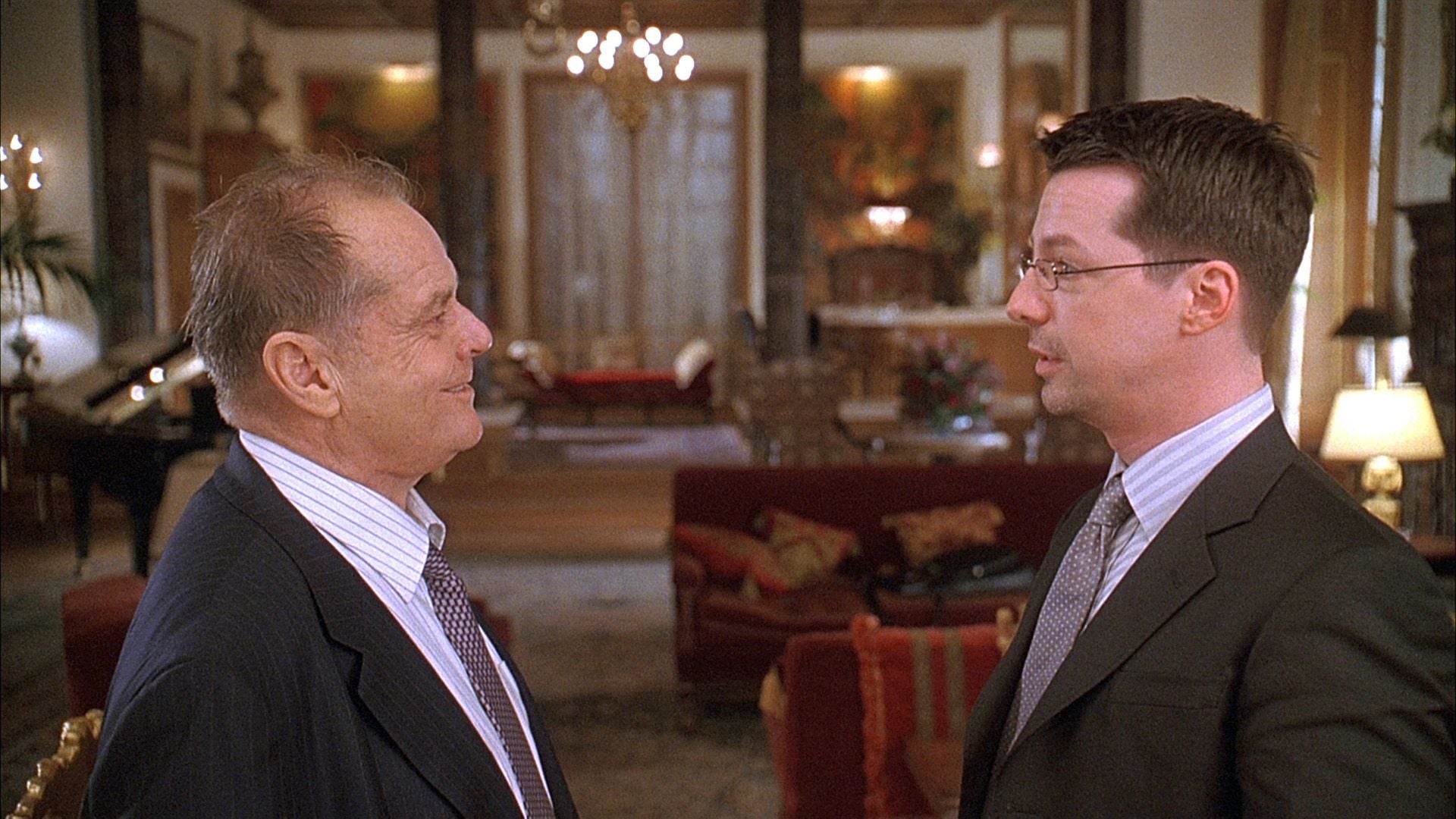

After Will & Grace, his next big thing arrived courtesy of a supporting role in The Bucket List, which saw two Hollywood heavyweights join forces with Hayes in tow. “It was pretty mind-blowing to be in the theatre and see the billing: ‘Starring Jack Nicholson, Morgan Freeman, and Sean Hayes,’” he says. Only years before, he had been paid $100 to dance the Charleston at a lavish Beverly Hills mansion party where Nicholson was in attendance. “It was so dumb,” he laughs. Released in 2007, the feelgood dramedy was one of Nicholson’s final roles before unofficially retiring in 2010. What was it like working with the screen legend? Hayes is oddly elliptical in his answer. “It was pretty… well, I mean, what I can say in this interview is that it was a wonderful experience.”

But back to Levant: plenty of people will have an Oscar in their life. The play’s Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Doug Wright said the pianist reminded him of his own “outrageous, brilliant” father, who was bipolar. Hayes is more coy. “People in my family that have struggled with mental health issues, including myself – but I don’t have severe mental health issues, although Scotty [his husband] would argue that’s probably not true – but yes I’ve been around it my whole life.”

Levant’s sharp-witted outbursts on Tonight with Jack Paar were shocking in their day, celebrated for their candour. “We live in a world now where everybody’s questioning what you can and can’t say, because you’ll be cast aside because of stating your opinions, and the backlash – especially in comedy – but I think it all depends on the messenger,” Hayes says. “There are still comedians who are brave enough to do jokes or have opinions about what they believe is true, and they’re unapologetic about it, and whether you agree with them or not, they’re fearless. And I think Oscar was fearless. And I think part of how he coped with his mental health issues was talking about them publicly. I’m sure it was a form of therapy for him.”

Hayes is in therapy – and loving it. “Mostly because my husband is sick of being my therapist,” he laughs. Another form of therapy for him is SmartLess, the podcast he hosts with Jason Bateman and Will Arnett that has steadily grown its audience into the millions. “I’m pretty open and honest. I talk about a lot, including my health problems [Hayes has atrial fibrillation, a condition that causes an irregular and rapid heartbeat]. I think it’s healing for me to just talk about it, whether to two people or 20 million people.”

Speaking to Hayes, you can tell this is a man in therapy. There is a peaceful acceptance in the way he talks about how things have gone and the way they will go. When I ask if he hopes his Tony and Good Night, Oscar will yield similarly fulfilling opportunities in the future, he says plainly: “Fine if so. Fine if not.” When he gets home to Los Angeles, Hayes plans to make an album on the piano. “For no other reason than to just do it. I don’t care if anybody buys it.”

‘Good Night, Oscar’ runs until 21 September at the Barbican Theatre; tickets here