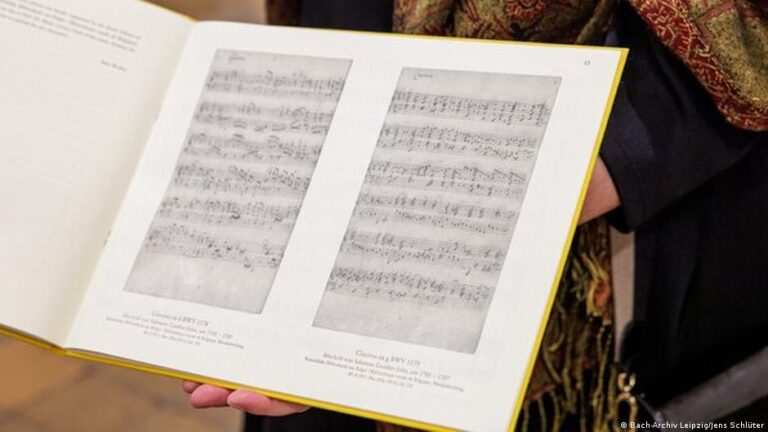

Peter Wollny has known the Ciacona in D minor and the Ciacona in G minor for more than 30 years now — ever since he discovered the organ works at the Royal Library of Belgium. The handwritten manuscripts were from an unknown writer; undated and unsigned.

Yet Peter Wollny — now director of the Bach Archive in Leipzig — had a sense his discovery could actually be a hidden treasure, composed by Johann Sebastian Bach. His meticulous hunt for clues began. “To confirm the pieces’ identity, I searched for a long time for the missing piece of the puzzle,” he remarked at the official ceremony for the newly discovered works. “Now, we have the whole picture.”

Performing the new Bach pieces

The two secular organ works have now been performed for the first time in 320 years.

They were performed at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig — where Bach was cantor for 27 years, from 1723 until his death in 1750 — by renowned organist and conductor Ton Koopman. The president of the Bach Archive said he was proud to perform them. “These pieces came out of nowhere, and who other than Bach could be their composer?”

Stylistically, many musical clues pointed toward Bach. The melodic accompaniment in the bass, for instance, which suddenly jumps to an upper register, or the extensive fugues.

Musicologist Peter Wollny attributes these stylistic characteristics as unique to Bach. He was able to uncover even more clues while working on a project on Bach’s family for the Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities. He turned up a letter that helped him identify the scribe who had copied the works. A close examination of the handwriting quickly confirmed it as Salomon Günther John — one of Bach’s pupils.

The 75th anniversary of the Bach Archive

It’s rare to find new pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach. Wolfram Weimer, Germany’s Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, called the discovery a gift: “It’s a wonderful interplay of excellence, scholarship and passion for music.”

While the new works will remain at the Royal Library of Belgium, Peter Wollny told DW that the Bach Archive has even more treasures in store. “I’m very proud to say that we own the second-largest collection of Bach manuscripts in the world, after the Berlin State Library.”

The archive’s most treasured possession are the original scores of Bach’s choral cantatas for the St. Thomas Choir. Manuscripts from other collections and publishers are also held at the archive. Loans from the Breitkopf & Härtel music publishing house, for instance, who have also just released the newly discovered sheet music.

“Some say we at the Bach Archive are living in an ivory tower,” Peter Wollny said at the ceremony. “If that’s true, it’s an ivory tower with two windows,” one of those being the museum’s interactive public archive, the other being Leipzig’s yearly Bachfest, which draws some 70,000 visitors from around the world.

Each discovery a breakthrough

One of the Bach Archive’s most significant projects is the New Bach Edition, developed together with the Bach Institute in Göttingen. From 1951 to 2007, researchers from around the globe worked on over 100 collections of sheet music. The historical and critical edition of Bach’s complete works was accompanied by additional texts going into the history of the pieces, as well as the research sources. “This set a new standard for many other collected works, which were modeled on the Bach collection,” says Henrike Rucker, who curated an exhibition on Bach research.

The New Bach Edition project led to another breakthrough: the dating of Bach’s famous Leipzig cantatas. The manuscripts had been left undated by Bach, but by examining watermarks in the sheet music and his letters of the time, the researchers were able to determine when the pieces had been created. They found out that Bach had written all of his famous cantatas from his time in Leipzig in the first four years. Entire biographies had to be re-written following the discovery. “He composed new cantatas every week, and the two passions, which is an incredible achievement,” Rucker told DW.

The ‘Berliner Singakademie’ in Kyiv

Following the war, much of Bach’s sheet music was scattered throughout the world, or disappeared completely.

Since the 1990s, some of the sheet music and collections have found their way back to Leipzig — like the “Sing-Akademie zu Berlin” archive, which was rediscovered in Kyiv in 1999. The Russian army had taken the pieces back to the Soviet Union.

“For 40 years, no one knew where the sheet music was,” explains Henrike Rucker. The collection contains pieces by Bach’s family — in particular his son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach — that up until then had been left incomplete. “And that took research on Bach’s family to a new level,” adds Rucker. The manuscripts have now been used to piece together an edition of the complete works by Bach’s eldest son.

Kulukundis collection worth $12 million

When it comes to uncovering new treasures, good relationships pay off, too. Musicologist Peter Wollny has long maintained ties with New York-based collector Elias Kulukundis. At once owner of a shipping company and music expert, he has specialized in works in the transitional period from the 18th to 19th century.

The collection had already been on a 10-year loan to the Bach Archive. For the establishment’s anniversary, Elias Kulukundis officially signed it over as a gift.

Valued at around $12 million (€10 million), his collection is the most valuable gift the Bach Archive has ever received. “It’s a unique collection of letters, autographs, prints and other documents relating to the lives and work of the four Bach sons,” Wolly explains. These include the opera “Zanaida” by Bach’s son, Johann Christian Bach — which was thought to have been lost.

Unsolved Bach mysteries

Numerous mysteries surrounding Johann Sebastian Bach’s work remain unsolved. Many of his pieces librettists remain unknown to this day. Far from all of the copyists who penned Bach’s sheet music have been identified. That said, with this new discovery, one more copyist has been revealed: Salomon Günther John.

For the longest time, little was known, too, about the women in Bach’s family. In 2024, the Bach Museum addressed the history of women in the Bach line, as they also contributed significantly to the family’s flourishing musical legacy.

The Second World War saw the loss of many important manuscripts — which have to this day never been recovered. “Much has also been found again,” says Peter Wollny — like the discovery in Kyiv. Other documents were found in other former Soviet storage sites. Many public and university libraries only recovered their inventories of manuscripts in the 1990s.

There is one discovery that would really get Wollny excited: “It would be such a sensation, on the scale of the discovery in Kyiv, if the library of the old St. Thomas School could be found again. If it still exists. Then, a similar flood of new findings could await us.” Wollny’s detective skills might yet one day lead him to it.

This article was originally written in German.