Michael Shannon is musing about his return to theatre, in a low Midwestern drawl that rumbles along like a Chevy. “There are times on stage where it seems like it’s just kind of as fulfilling as life gets…” the star of Man of Steel and Boardwalk Empire tells me, “and there are times where you do not want to be in front of 300 strangers, torturing yourself… and everything in between. But when it hits, it’s a very unique feeling. You can’t find it out walking down the street, or doing anything else. It’s a religious feeling.”

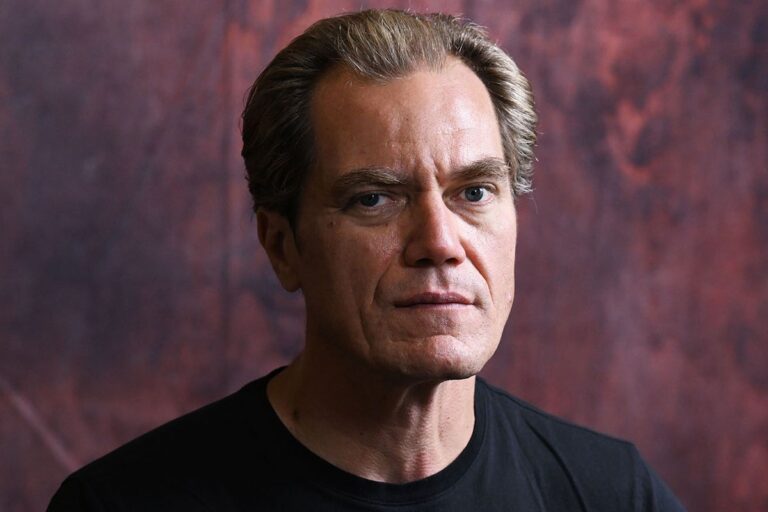

We’re in his cramped dressing room at the Almeida, where Shannon is playing Eugene O’Neill’s haunted alcoholic Jim Tyrone in A Moon for the Misbegotten. His face is all shadowy hollows and sharp angles, brow permanently furrowed. Some roles have a powerful emotional effect on him, he admits, but he tries hard to shed them afterwards. “If I were still invested in every part I ever played in my life, I’d probably be in a straitjacket,” he says.

Today he is dressed in a more leisurely T-shirt and shorts combo. The 50-year-old is lean and sinewy, carrying his height like an inconvenience, his long frame folded slightly inwards. He’s taciturn and measured, in a way that could be unnerving were there not flickers of deadpan charm. For much of our early exchanges, his eyes, capable of conveying such intensity, remain closed. He has an Albert Einstein quote tattooed on his arm: “No problem can be solved by the same level of consciousness that created it,” it reads.

You get the impression that, while he is calm and meticulous on the surface, he might at any moment boil over into that next level of consciousness. But maybe that’s just because we’re so used to seeing him flip out so convincingly on screen. Indeed, throughout his career, Shannon’s currency has been an electrifying knack for the bottle-up-and-explode school of acting. His characters are often complex studies in inner conflict.

Watch him go nuclear, for example, in 2011’s Take Shelter – perhaps the hardest role to shed of them all – as a man slowly unravelling under apocalyptic visions. Or think of his outstanding breakthrough performance in the Fifties-set Revolutionary Road (2008), for which he was Oscar-nominated as a mentally disturbed savant who punctures the Wheeler family’s suburban ennui. Then there’s his maniacally pious G-man in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire; the reptilian property mogul in 99 Homes (2014); and a laconic, Stetson-wearing Texas lawman in Nocturnal Animals (2016), to which he brought a dry, macabre humour en route to another nod from the Academy.

Shannon’s latest role, in A Moon for the Misbegotten, has received similarly rave reviews. Starring opposite British actors Ruth Wilson and David Threlfall in O’Neill’s sequel of a sort to Long Day’s Journey Into Night, he is unhurried and utterly engrossing, playing Tyrone as a man whose self-disgust has metastasised into something that consumes him from within. The Independent called the production “luminous”, proclaiming that “misery never shone so bright”.

I was very reluctant to do the ‘The Flash’. Zack Snyder had been excommunicated from the whole Warner Bros empire, and that left this sour taste in my mouth

It’s a sequel for Shannon, too, who played Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey Into Night on Broadway in 2016. The follow-up is so rarely performed that when the chance came up, he says, it felt “like fate or destiny” and he jumped at it, despite knowing how emotionally demanding the role would be. “There’s no denying that [O’Neill] is excavating some extraordinarily painful truths from himself,” says Shannon, “and trying to give them to us.”

I wonder how he’s found working with Wilson and Threlfall, and whether he sees differences between actors from opposite sides of the Atlantic. The world feels “so much more sewn together” these days, he suggests. There is a notion, says Shannon, “that British theatre is more kind of elevated or sophisticated, or cerebral. And that the Americans are more primal or guttural or whatever, but that all just feels to me like a cliché. I feel like great actors are great actors, no matter where they’re from – and usually, typically, what makes them great is a willingness to explore very dark, and sometimes painful, territory with a sense of truth.”

.jpeg)

Of course, greatness also comes from putting in the yards, he notes. The word “work” runs through our conversation, a persistent motif, which may explain why Shannon feels a frisson of belligerence when DC fans queue up outside the Almeida asking him to sign pictures of General Zod, his Superman villain in 2013’s Man of Steel. “I let them know that I don’t appreciate it,” he says, “because I’m here to work.”

He’s long had what one might call a detached relationship with fame. “Don’t get me wrong,” he explains. “The first time somebody stops you on the street and says, ‘Hey, man, I saw you in a movie,’ that’s cool. You’re like, ‘Oh, wow.’ But 20 years later, and that’s now happened like 3,000 times or whatever, you’re like, ‘Jesus.’”

He appreciates that, with long-running TV shows such as Boardwalk Empire (a series he once admitted he’s barely watched), “people spend a long time [with it], and they really get kind of obsessed”. But with Zod, he says, “I’m not here to sign a bunch of pictures that they can sell on the internet, so that’s a drag.”

Zod remains a fascinating character, though, and Shannon recognises the cultural significance of this representative of a civilisation that has ruined its own planet and now wants to colonise another. Shades of Elon Musk and his plans for Mars? “Well, yeah, that occurred to me from the get-go,” he says. “It’s one of the reasons I wanted to do it. Some people, I think, thought I was succumbing to the comic-book universe and taking the paycheque. But I actually thought it was an important story. And you don’t often get to tell stories like that with a guaranteed international audience. So it was kind of a grand slam, as we say in the States. I got to tell my subversive story and be in a big Hollywood blockbuster, all at the same time.”

Shannon reprised the role of Zod in 2023’s The Flash, a film beset with difficulties. “I was very reluctant to do the movie,” he says, “just because of the way that Zack Snyder had kind of been excommunicated from the whole Warner Bros empire. And that left this sour taste in my mouth.” Snyder, who had directed Man of Steel, departed 2017’s Justice League midway through production after the death of his daughter. While DC later allowed him to develop his own, four-hour-long director’s cut of the film in 2021, his hopes for a planned trilogy of Justice League films never came to fruition, and the filmmaker parted ways with the franchise that year. “I did not like the way they treated him at all,” Shannon continues. He took the role in The Flash because he got on with director Andy Muschietti, but re-subscribing to the superhero franchise took its toll. “There were several days where I thought, ‘I’m not doing this again.’”

Shannon is famously outspoken. In 2017, he described the environment as screwed, the iPhone as a narcotic, and suggested that the Republican Party has zero compassion for human life and that people who voted for it have “s*** for brains”. What is his current level of existential angst? “I do think technology is frightening,” he says; politically, though, he’s entered a new phase. “The rage has come and gone.” For the sake of his sanity, he explains, he’s had to narrow his focus, learning to take things one day at a time and stay present. “I’m conscious of the limited list of things I actually have any control over – like doing this play, which may be soothing or helpful to somebody. Or the way that you conduct yourself in the world, trying to live with compassion. I didn’t find the rage particularly helpful. So I’ve kind of let go of that. It’s not like I don’t care any more. I still care, but I have to think about what’s healthy for me.”

Over the past two decades, Shannon has found a release in music, first with his indie band Corporal – who released a halfway decent lo-fi album in 2010 – and then in performing entire albums by some of his favourite artists. Lately, Shannon and collaborator Jason Narducy have been in demand. After covering a string of albums by the likes of Bob Dylan, Neil Young and The Smiths, they recently embarked on US tours playing full-album renditions of REM’s debut Murmur and the band’s 1985 LP Fables of the Reconstruction. “We love doing it, so we keep doing it. And now we have seven or eight dates here in the UK after the play closes.” The experience of being a frontman on stage, he says, “took me back to when I just started acting, you know, and the excitement of that”.

At first, Shannon once admitted, acting allowed him to channel his angst. It was an outlet. “I was miserable and crazy and wanted to be someone else,” he told The New York Times in 2010. Uncertainty and instability were part of his upbringing: his parents were each married five times, divorcing one another when he was still a kid. Growing up, he would shuttle between his mother’s home in Kentucky, where he was born, and his father’s up in Evanston, Illinois, where he would start high school. As an adolescent, he became increasingly erratic; he was sent to a child psychologist, but responded to the man’s questions, reportedly, by trashing his bookshelf and storming out.

Just as O’Neill needed to write about his family to deal with his own feelings, does acting still help Shannon with his? “I started acting about 35 years ago, so if something hadn’t changed in that time, that would be a problem,” he says with a laugh. “Now it’s kind of my job. You know, the way that people have jobs; it’s what I do. What’s become the most important thing is telling the story.”

He’s had a career, he tells me, that’s “all over the shop”. “There was no catapult, you know, the meteoric rise to whatever.” But his “slow and steady” climb has made him one of the most admired actors of his generation, and he recently moved behind the camera for his directorial debut, Eric LaRue, adapted from Brett Neveu’s 2002 play. Judy Greer and Alexander Skarsgård star as parents whose teenage son murdered three classmates in a school shooting. Though the film is yet to be released in the UK, the US reviews were positive, with IndieWire calling it a “quiet triumph” that “beautifully unpacks how the sins of the son impact both the father and mother”.

Directing the film gave Shannon a greater appreciation of “what’s important” about acting on camera, which he says can “be a horrifying and very awkward experience”, although he’s grown less anxious about it over the years. It helped him to see “what you need to get in a way that I didn’t use to understand”.

In the past, he’s been scathing about TV and its corporate overlords – “You don’t even know who’s freaking in charge,” he says, describing the layers of conglomerated ownership. “There’s a bunch of people running around claiming to be in charge, but they aren’t. There’s somebody over them – and whether you meet them, ever, or not, is a big question mark. It’s disheartening, but people remind me it’s always been that way; even in the old days, studios were financed by big money.”

It’s a medium that gives the actors very little control, he explains. “It can be hard to deal with… Sometimes you work really hard on something, and you see it get kind of mutated into something you’re not super happy about, but you still get paid.

“That’s the great thing about theatre – I know when I’m doing a play with these people that what you’re seeing is what we’re doing. There’s no intermediary. There’s nobody coming in and saying, let’s cut that part out, or cut away from him when he makes that face, or whatever.”

Shannon unfurls, his eyes fixing me with a stare. “Theatre is the actor’s domain,” he says. “We’re in charge.”

‘A Moon for the Misbegotten’ runs at London’s Almeida Theatre until 16 August. Tickets can be bought here. Michael Shannon and Jason Narducy play London’s The Garage on 22 August, with tickets available here