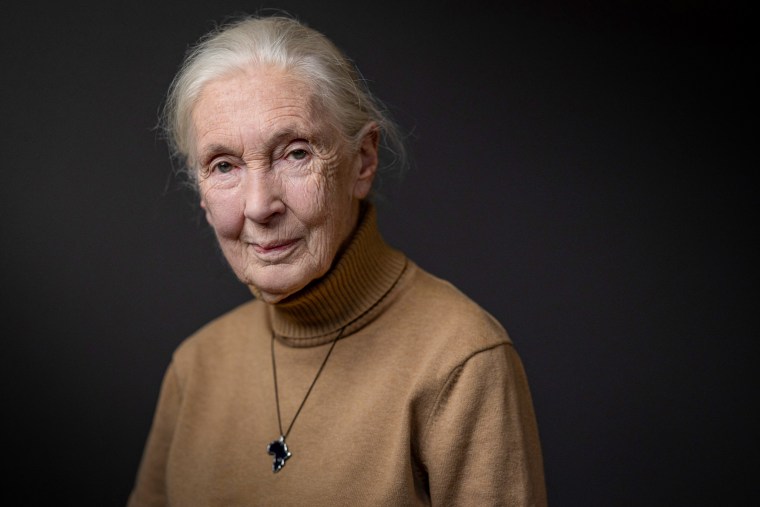

Jane Goodall, a renowned researcher who documented the behavior and social lives of chimpanzees and later became a leader of the animal conservation movement, died Wednesday.

Goodall was 91. She died of natural causes while she was in California as part of a speaking tour, the Jane Goodall Institute announced in a statement.

“Dr. Goodall’s discoveries as an ethologist revolutionized science, and she was a tireless advocate for the protection and restoration of our natural world,” the statement said.

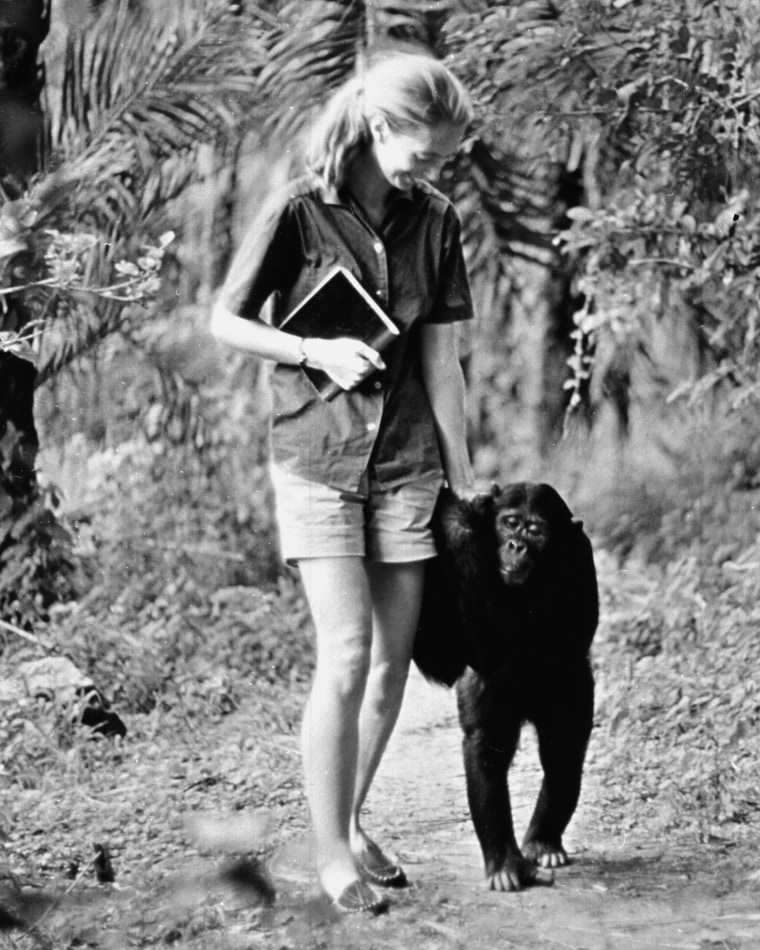

Goodall, who was born in Britain, became famous first for her pioneering work with chimpanzees in Tanzania in the 1960s. She fastidiously documented how the animals lived and interacted in research that would continue over several decades.

She took an “unorthodox approach” to her research of chimpanzees, according to the foundation, by “immersing herself in their habitat and their lives to experience their complex society as a neighbor rather than a distant observer.”

Goodall published a study showing that chimps used sticks as tools to fish for termites, which challenged the prevailing idea that humans were the only species capable of using tools. She also documented the animals’ communication abilities and complex social behaviors, and she helped establish that they eat meat and sometimes fight with one another.

“She really established all these fundamentals on chimpanzee behavior we’ve been able to elaborate on in these past few decades,” said Elodie Freymann, a primatologist who is a postdoctoral researcher at Brown University.

Robert Seyfarth, a professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania who studied primate behavior, said Goodall’s death “marks the end of an era.”

“Her careful, detailed observation and reports really got a whole generation of us — me included — and many others interested in this as a field of scientific endeavor,” Seyfarth said.

He said Goodall was among the first researchers to make close observations of chimpanzees as individuals with personalities and quirks, at a time when other scientists were not trained to observe such specific details.

“Her perceptions of the emotions of chimpanzees was pathbreaking,” he said, adding that Goodall was an “honest chronicler” of the species’ behavior — both of the ways they cared for one another and of their fighting and killing.

“Her agenda was to have people understand chimpanzees in all their complexity,” Seyfarth said.

As Goodall’s career progressed and she saw how habitat destruction and illegal trafficking threatened the survival of chimpanzees, she made conservation and animal welfare a focus of her work.

As the Jane Goodall Institute, which she founded in 1977, put it, Goodall “went into the forest to study the remarkable lives of chimpanzees — and she came out of the forest to save them.”

Ingrid Newkirk, founder of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, said in a statement that Goodall helped the organization “end the confinement of chimpanzees locked in barren, solid metal chambers for experiments.”

Goodall was just 26 when she visited Tanzania for the first time to study chimpanzees. She began her career without scientific training, after Louis Leakey, a prominent Kenyan-British anthropologist, hired her to record her observations of chimpanzees. Goodall would later receive a doctoral degree from the University of Cambridge.

In an interview on the podcast “Call Her Daddy” this year, Goodall told host Alex Cooper that her first expedition was on a shoestring budget funded by a philanthropist.

Goodall had six months of funding, and the first four months were fruitless as the primates were too skittish to allow her to get close enough for observation. But one of the animals finally adjusted to her presence long enough for her to make the breakthrough discovery that chimpanzees create and use tools.

“The reason why this was so exciting was because, at that time, it was thought by Western science that only humans used and made tools. We were defined as man, the toolmaker,” Goodall recalled. “And so when I wrote to my mentor, Louis Leakey, he was just so excited.”

That discovery piqued the interest of — and funding from — National Geographic and ultimately changed the course of Goodall’s career.

As Goodall became a prominent figure, she used her celebrity to advance animal causes and public interest in science. She wrote dozens of books about her interactions with chimpanzees, including many children’s books.

Freymann, the primatologist, recalled dressing up as Goodall for Halloween in the fourth grade. Later, as a 19-year-old intern at the Jane Goodall Institute in Washington, D.C., he read through piles fan mail from children, he said.

“I’m a primatologist because I had a hero I could look up to,” said Freymann, who is now 29. “She encouraged my entire generation to go out and do it. … She set the course of my entire life professionally and the values I believe in.”