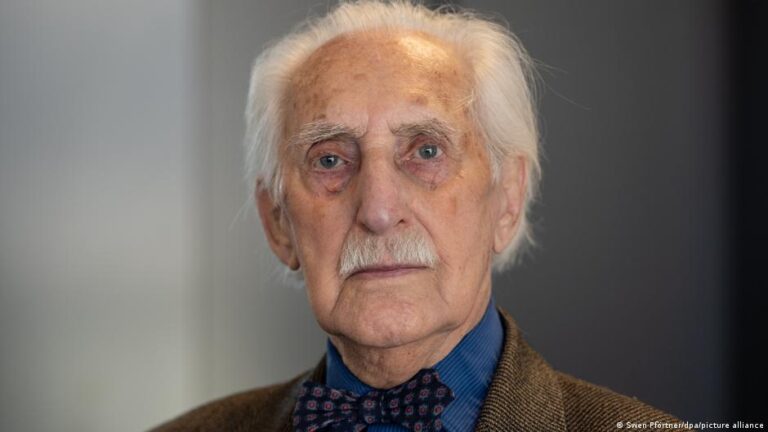

Leon Weintraub can still remember the day the Nazis marched into his Polish hometown of Lodz on September 9, 1939.

“There they came, seemingly endless rows of tall, healthy young soldiers in green Wehrmacht uniforms. The thought of the sound of their hobnail boots on the cobblestones still sends a cold shiver down my spine,” he tells DW. “They exuded so much power and would smash anything that stood in their way.”

Weintraub was only 13 then and had no idea what horrors awaited him. He lived in a poor neighborhood with his four sisters and his mother, who ran a small laundry service. His father had died when he was barely two-years-old. The tight-knit family relied on each other for support. Leon was a bright boy.

“Reading books and watching movies were like a peephole for me, allowing me to get a glimpse at another world,” he says.

Confined behind ghetto walls

Thanks to a scholarship, Weintraub was able to attend high school. However, this ended in February 1940, when he and his family were forcibly relocated to the Lodz ghetto, where 160,000 Jews were crammed together. Anyone who attempted to escape was shot.

The ghetto residents were subjected to hard labor. Leon worked in the metal department of an electrical workshop. The “Judenrat,” compulsory Jewish councils set up under Nazi occupation, told him that those who were useful to the Nazis had better chances of survival.

Many people in the ghetto died of disease and hunger. “So, the word ‘hunger’ has a very special place in my vocabulary, my mind, and my being,” says Weintraub. Today, people often say they’re hungry when they skip a meal, but “that’s not true hunger, that’s just increased appetite.

“For five years, seven months, and three weeks, except for one occasion, I literally suffered from starvation. I couldn’t fall asleep because of the painful pressure in my stomach, and I woke up with it. My only thought was how to get something to eat to fill my stomach.”

Deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau

In the summer of 1944, the ghetto was closed down. The district president of the region, Friedrich Übelhöhe, had already circulated a letter to Nazi leaders in 1939, in which he wrote: “The creation of the ghetto is, of course, only a temporary measure. I reserve the right to decide when and by what means the ghetto and the city of Lodz will be cleansed of Jews. In any case, the ultimate goal must be to eradicate this plague.”

Despite this, the residents of the ghetto were cynically promised that they would be allowed to work elsewhere for “the good of the Third Reich.”

Like many others, Leon Weintraub was deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. The Nazis claimed it was simply another ghetto.

“Then the freight train arrived, more suited for transporting cattle than people,” Weintraub recalls. “We were crammed in so tightly that we could only stand. The doors were locked; there was no food, nothing to drink. Night fell, then day broke again, and then night fell once more.” The stench from the bucket used for the toilet overwhelmed everything.

At one point, the doors were thrown open, and someone shouted, “Out, out.” Weintraub recalls that he still didn’t realize where the Nazis were taking them. He called out to his mother, “See you inside.” But he soon realized that he had ended up in another ghetto.

Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed that the barbed wire fence was electrified. Weintraub saw his mother for the last time during the so-called “selection.” The SS officers issued life and death decisions with a simple gesture: “Thumb to the right: unfit for work; thumb to the left: death on hold,” Weintraub recounts. His mother was killed in the gas chamber later that same day.

For 18-year-old Leon, the thumb pointed to the right. “And then the process of dehumanization began,” he recalls. The people were stripped naked, showered, shaved, and disinfected. “We were robbed of all human will. They controlled us, and we had no choice but to follow orders.”

Escaping the gas chamber

When Leon Weintraub thinks of Auschwitz, the smell of burnt flesh comes to mind above all else. “I had no idea,” he says, “that the tall chimneys, the thick black smoke, were burning human beings.” However, he says, he cocooned himself from the reality as a form of self-preservation: “Otherwise, I wouldn’t have been able to endure it.”

By sheer chance, he survived the death camp. The young inmates of Block 10, where he was held, were already scheduled to be sent to the gas chamber. When the guards were not around, Weintraub blended in with a group of naked prisoners who were being taken to work at the Gross-Rosen camp. They had just had their prisoner numbers tattooed on their arms. “When we got to the clothing depot, fortunately, no one checked me; otherwise, I would have been dead.”

The final image of Auschwitz that he carries with him is the corpse of a woman who’d committed suicide, her body hanging on an electric fence.

Survival against all odds and escape

The next stops for young Weintraub were the concentration camps at Gross-Rosen, Flossenbürg and Natzweiler-Struthof. The images of the Nazis’ sadistic atrocities are etched deeply in his memory: arbitrary brutal beatings inflicted on prisoners passing by, humiliation and the hanging of inmates.

“Every time I come to Flossenbürg, my legs tremble,” he tells DW. “I freeze for a few seconds because I am transported back to that winter, feeling that cold wind. The entire crowd moves across the roll call square. It’s an apocalyptic image.”

Shortly before the end of the war, Weintraub was transported on a train that was meant to be sunk in Lake Constance. However, the locomotive was shot at by French aircraft, and Leon managed to escape. When he encountered a French soldier, he realized that his ordeal was finally over. At that time, the 19-year-old weighed only 35 kgs and was suffering from typhus. He mourned the loss of his family until he learned by coincidence that three of his sisters had survived the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. “And that’s when I became human again. It was the beginning of my journey back to life,” he says.

Postwar life and remembrance

Weintraub chose to become a gynecologist and obstetrician after his experience with illness and death. He wanted to devote his life to bringing new life into the world.

In 1946, the British military government arranged for him to study in Göttingen, Germany, the land of the perpetrators. As a physician, he encountered firsthand the lack of valid scientific evidence for Nazi racial ideology.

In 1950, he returned to his homeland, but emigrated to Sweden by 1969 due to the growing prevalence of antisemitism in Poland. He began to advocate for the importance of remembrance, viewing it as a duty to his murdered family members and the millions of innocent victims. He warned that allowing their memory to fade would be akin to robbing them of their lives a second time.

That is also why he has chosen to preserve his testimony as a hologram.

“Barely a human lifetime has passed, and many young people today no longer know what the Holocaust was,” he says. “It’s terrible that there are people calling for pogroms once again, and that people are afraid to go out on the street wearing a kippah.”

Despite everything, Weintraub is an optimist: “I am convinced that at some point common sense will prevail and humanity will realize that it is time to stop accusing and fighting each other and to build a peaceful future together.”

This article was originally written in German. The interview with Leon Weintraub was conducted by Matthias Hummelsiep.