Inside a hall stretching more than 100 meters (about 330 feet), countless robots hum as lights blink and warning signals chirp. Currently, only about a dozen people are working on the floor, with the remaining work being handled by high-performance machines.

Journalists are rarely allowed inside this high-tech factory from China, and when they are, the rules are strict: no photos, smartphone cameras are taped over, and even short audio recordings require approval from a press spokesperson.

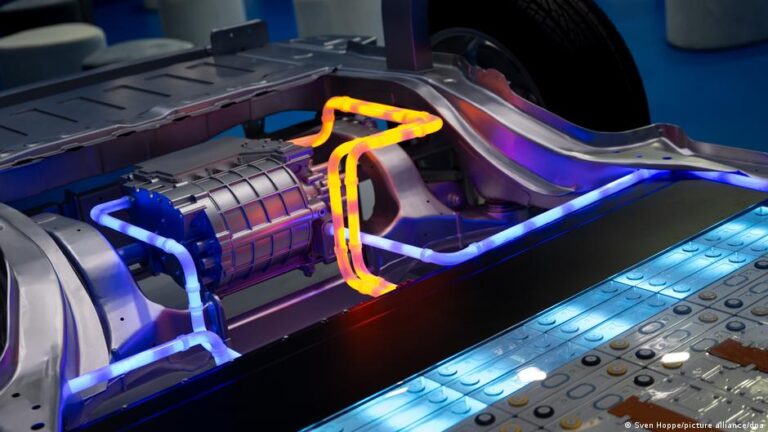

The plant shrouded in secrecy is not located somewhere in China, but in Arnstadt, a small town in the eastern German state of Thuringia. It belongs to Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL), the Chinese global market leader in electric vehicle batteries. The factory produces 14 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of battery capacity a year — enough for at least 200,000 electric cars — supplying, among others, European automakers.

For CATL, manufacturing directly in Germany shortens transport routes for heavy, flammable batteries and reduces geopolitical risks such as punitive tariffs. At the same time, the plant reflects the shifting trade relationship between China, Germany and the European Union.

How ‘Made in Germany’ helped China to the top

For decades, the “Made in Germany” label served as a benchmark for modern manufacturing standards in China. As early as the 1980s, Volkswagen’s joint venture in Shanghai, for example, impressed Chinese partners.

More than 20 years later, Germany doubled down on digitally networked production to boost productivity and efficiency under the banner of Industry 4.0.

By then, China’s manufacturing sector was already eager to shed its image as a low-cost producer and Germany’s Industry 4.0 initiative offered an opening.

In 2014, the two countries signed cooperation agreements, and in May 2015, Beijing unveiled a strategic plan called “Made in China 2025” aimed at modernizing its own industry to become a global leader in key manufacturing sectors.

Today, China has reached that goal in many areas, said Oliver Wack from the German Engineering Federation, VDMA, and has become a formidable competitor to Germany.

“In 2018, Chinese machinery manufacturers delivered goods worth €20 billion [$23.4 billion] to the EU. By 2024, that figure had risen to €40 billion, and this year it could reach €50 billion,” he told DW, noting, however, that Germany still exported more machinery to China than vice versa.

In sectors such as green tech the pressure is even greater, said Carlo Diego D’Andrea of the EU Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai. In a recent interview with German public broadcaster ARD, he said China’s solar and wind capacity, meanwhile, exceeds that of all other countries in the world together. China also dominated the global drone market with a 70% share, he added, and a similar dominance was emerging in the market of electric vehicles (EVs).

Technology transfer: China’s fast track to success

Shortly after announcing the “Made in China 2025” strategy a decade ago, Beijing rolled out a range of measures helping its companies to acquire cutting-edge technologies or even entire firms in Europe.

At the time, the Mercator Institute for China Studies already warned that while technology transfer could bring short-term gains, it posed long-term risks for Germany and Europe.

The 2016 takeover of German robotics company Kuka by China’s Midea Group appears to have proven the critics right.

Others played down the concerns, like Clas Neumann, then vice president of software maker SAP, who said in 2016 that China would not be able to overtake Germany in key industries in the short term. He thought it would take “at least 20 to 30 years” for the Chinese to master those processes and technologies.

China, however, invested heavily in research, with so-called R&D spending jumping from 1.37% of GDP in 2007 to 2.56% in 2022, largely financed by corporate profits and government subsidies. State support even quadrupled between 2014 and 2024, now almost matching research subsidies in the United States, the world’s biggest R&D spender.

Camille Boullenois, a China expert at New York-based consultancy Rhodium Group, said massive subsidies enabled Beijing to achieve its “Made in China 2025” goals like reducing dependence on Western technology and gaining market share. Even in areas where China still lags, such as aerospace or advanced semiconductors, it could catch up “within a few years at the current pace,” she told DW.

Boullenois, however, criticized the subsidy-driven approach as unsustainable, as it has led to “enormous waste and weaker economic growth.”

She believes such “overinvestment” in key technologies came at the expense of much-needed structural reforms, contributing to weak domestic consumption. “China’s economic system is heavily production-oriented. Companies tend to overinvest, leading to capacity that exceeds domestic demand. These excess capacities flood export markets and pose a challenge for European firms,” she explained.

When ‘Made in China’ comes from Germany

However, Boullenois said cooperation with China can be profitable for both sides if Chinese companies produce locally in Europe.

The CATL battery plant in Arnstadt might be a case in point, as only about 10% of the more than 1,700 employees come from China. Moreover, the company works closely with local universities and chambers of commerce to develop young talent, and operates a training center where around 20 apprentices are currently learning trades such as mechatronics.

The site has also attracted the Fraunhofer Institute, which has built its Battery Innovation and Technology Center (BITC) there, giving CATL engineers and German researchers the opportunity to jointly work on next-generation battery technology.

Roland Weidl, head of Fraunhofer’s research center, told DW that the cooperation is “a win-win situation for industry, research, and the economy. As Fraunhofer and CATL were both technology leaders in different areas, the cooperation works because “both partners believe they can benefit.”

Boullenois of the Rhodium Group notes that Chinese firms once benefited heavily from technology transfers from Western companies. Europe, she said, can draw lessons from that experience by leveraging its internal market to attract investment, build local value chains, and encourage technology exchange.

The EU is currently considering setting conditions for Chinese companies investing in Europe, including clear rules on technology transfer, local value creation and employment.

This article was originally written in German.