Mention “perfume” and one might first envision fragrant liquids in fancy flacons.

Yet the name itself, derived from the Latin “per fumum” — meaning “through smoke” — indicates that what we understand as “perfume” today differs vastly from its origins and uses among our ancestors.

Its history is also a study in scientific breakthrough, knowledge transfer, trade expansion, colonialism and natural resource extraction, as well as latter-day Eurocentric marketing.

Scent as old as time

Britannica states that the ancient Chinese, Hindus, Egyptians, Israelites, Carthaginians, Arabs, Greeks and Romans were all reportedly familiar with perfumery. References to perfume and its use are also found in the Bible as well as the Hadith (the sayings or actions) of the Prophet Muhammad.

Early perfumery — dating back over 4,000 years to ancient Mesopotamia — involved burning aromatic substances like frankincense and myrrh, in the belief that the upward curling smoke bridged earth to the divine.

In fact, the earliest recorded “nose” — or highly skilled master perfumer — was a woman named Tapputi, a chemist whose works in Mesopotamia were documented on a cuneiform tablet dated around 1,200 B.C. “Tapputi was a muraqqitu, a distinct professional category of specialist perfumers attached to Assyrian and Babylonian courts … her importance lies in attesting to women occupying a high‑status, ‘perfumistic’ role in royal courts,” perfumer and historian Alexandre Helwani tells DW.

According to archeo‑chemist Barbara Huber, whose research focuses on human-plant relationships throughout history, “perfume” came to encompass over time a wide range of fragrant materials and practices: burning incense and aromatic woods, scented oils, balms, unguents, and even cosmetics.

“Many of these were used not just for personal adornment, but for ritual purposes, offerings to deities, purification or healing. The boundaries between perfume, medicine and cosmetics were often blurred,” Huber tells DW.

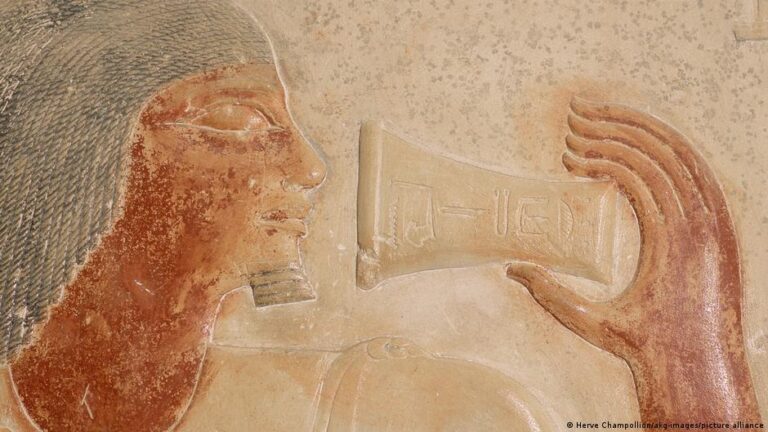

In ancient Egypt, aromatic oils and resins were central to rituals and mummification, while in India, sandalwood paste was applied to the skin, jasmine braided into hair, and saffron woven into clothing — a layered sensory practice sanctifying the body itself.

Recent research even found that Greco‑Roman sculptures of gods and goddesses were “perfumed” with scented substances to make them more lifelike.

From smoke to distillation

What began as incense and balms was transformed in the Arab world into liquid distillations during the Islamic Golden Age. In 9th‑century Baghdad, the polymath Al‑Kindi authored “The Book of the Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations,” the first comprehensive manual on perfumery.

A century later, Persian polymath Ibn Sina (known in the West as Avicenna) refined steam distillation, for extracting “attars” (or essential oils) from flowers, particularly roses that became a model for later perfumers.

Together, they established many of the fundamental techniques and methodologies on which the modern fragrance industry is based.

How the West was won over

These advancements reached Europe through several routes. Al‑Andalus — the then Muslim‑ruled parts of Spain and Portugal between the 8th and 15th centuries — served as a scholarly bridge, where scholars based in Toledo translated Arabic texts into Latin. At the same time, Mediterranean trade carried rose water and spices into ports like Venice and Genoa, while the Crusades exposed Europeans to Arab medical and aromatic practices firsthand.

To be clear, Europe was no stranger to perfumery. The Romans had scented baths and oils, and medieval nobles used herbs, pomanders, and incense. In the Middle Ages, perfume served practical and symbolic needs: Doctors stuffed herbs into their bird‑beaked masks to filter out the “bad air” or miasma believed to have caused the Black Death; Louis XIV of France had his favorite orange blossom water springing out of the fountains at the Palace of Versailles; and scented gloves not only masked odors but were fashionable accessories.

But the Arab world’s advanced techniques and rich ingredients reignited and transformed European perfumery into the sophisticated industry it would become, using alcohol as a base to create lighter, longer‑lasting perfumes.

‘Eau de Colonialism’

As European perfumery flourished, notably in France, colonial expansion supplied the ingredients that sustained the burgeoning industry.

“Marketing images tend to present raw materials as timeless gifts of nature, often framed in a vaguely post‑colonial exoticism. The complex questions of land tenure, labor conditions, pricing and environmental impact are usually omitted,” explains Alexandre Helwani.

One striking example is vanilla. Brought to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century, it became a major colonial crop in the Indian Ocean. Helwani cites the story of Edmond Albius, an enslaved boy on Réunion (formerly Bourbon) Island who, at age 12, discovered the practical method for hand-pollinating vanilla orchids in 1841.

“Had it not been for him, vanilla would have remained a scarcity … In a world of patented technologies, I often wondered how big of a billionaire Edmond Albius would have been, had he not been enslaved,” Helwani notes, underscoring how “when we speak of the ‘history of perfume’ we are simultaneously speaking of the history of empires, of trade and of colonialism.”

A whiff of Eurocentricity?

Over time, European perfume houses became central to branding and marketing, cementing an association of refinement with European aesthetics.

“While the foundational ingredients come from diverse global regions with rich historical traditions of aromatic use, the presentation and marketing narratives often tend to be Eurocentric,” says Barbara Huber.

Thus, some European perfume houses classifying fragrances as “Oriental” have also attracted considerable flak. As a change.org petition objecting to such categorization notes: “The ‘Orient’ attempts to encapsulate a vast region, including the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, where many ancient perfumery practices and raw materials originated. The consistent use of the term to summon the exotic and redolent erases the imperialism and Islamophobia that continue to destabilize these areas of the world today.”

Thus, a shift since the 2000s in marketing has seen “amber” being used for warm, spicy scents.

PerfumeTok’s influence

Today, global audiences can easily find out about once-niche or regionally specific fragrances through TikTok influencers and their unpacking reels.

An early viral sensation on PerfumeTok — TikTok’s hashtag dedicated to fragrance — was Phlur’s “Missing Person,” which sold out in 2022 and amassed an initial waiting list of more than 200,000 people in the US. It even opened the floodgates (literally) of emotional reels featuring people who were reminded of loved ones after getting a whiff of the scent.

Meanwhile, young entrepreneurs in India are reframing ittars (essential oils) created through centuries‑old methods as sustainable luxury through Instagram and digital storytelling, demonstrating how social media can reconnect consumers with traditions that colonial trade may have once obscured.

In all, perfume’s history — like its top, heart and base notes — is multifaceted. And just as no single perfume can capture every scent in the world, no single retelling can encompass the diverse histories of fragrance.

As Alexandre Helwani says, every spray of perfume carries a load of heritage. “That’s what I love about perfume: It’s a very small gesture on the skin with an enormous, layered history behind it.”

Edited by: Elizabeth Grenier