Some 12 miles southwest of the city of Buenos Aires is a remarkable settlement called Ciudad Evita. It was founded in 1947 by the then-president of Argentina, Juan Perón, in tribute to his wife, Eva. What’s remarkable about it is that the entire street grid is designed to look like her profile – meaning that passengers flying in and out of the capital can, if they look closely enough, make out her nose and chignon bun from 10,000ft in the air.

This feat of urban planning is just one example of how Eva Perón’s legacy is kept alive in her homeland, where museums and monuments have been erected in her honour. “My biggest fear in life is to be forgotten,” Eva once said – though she really needn’t have worried.

Internationally too, Argentina’s former first lady has inspired many a film, play, novel and TV show. In 2022, Santa Evita on Disney+ dedicated itself to telling the story of Eva’s corpse after her death from uterine cancer aged 33. As a testament to her cultural pull, Eva featured in an episode of The Simpsons in which precocious Lisa channels her in becoming head of her school’s student body.

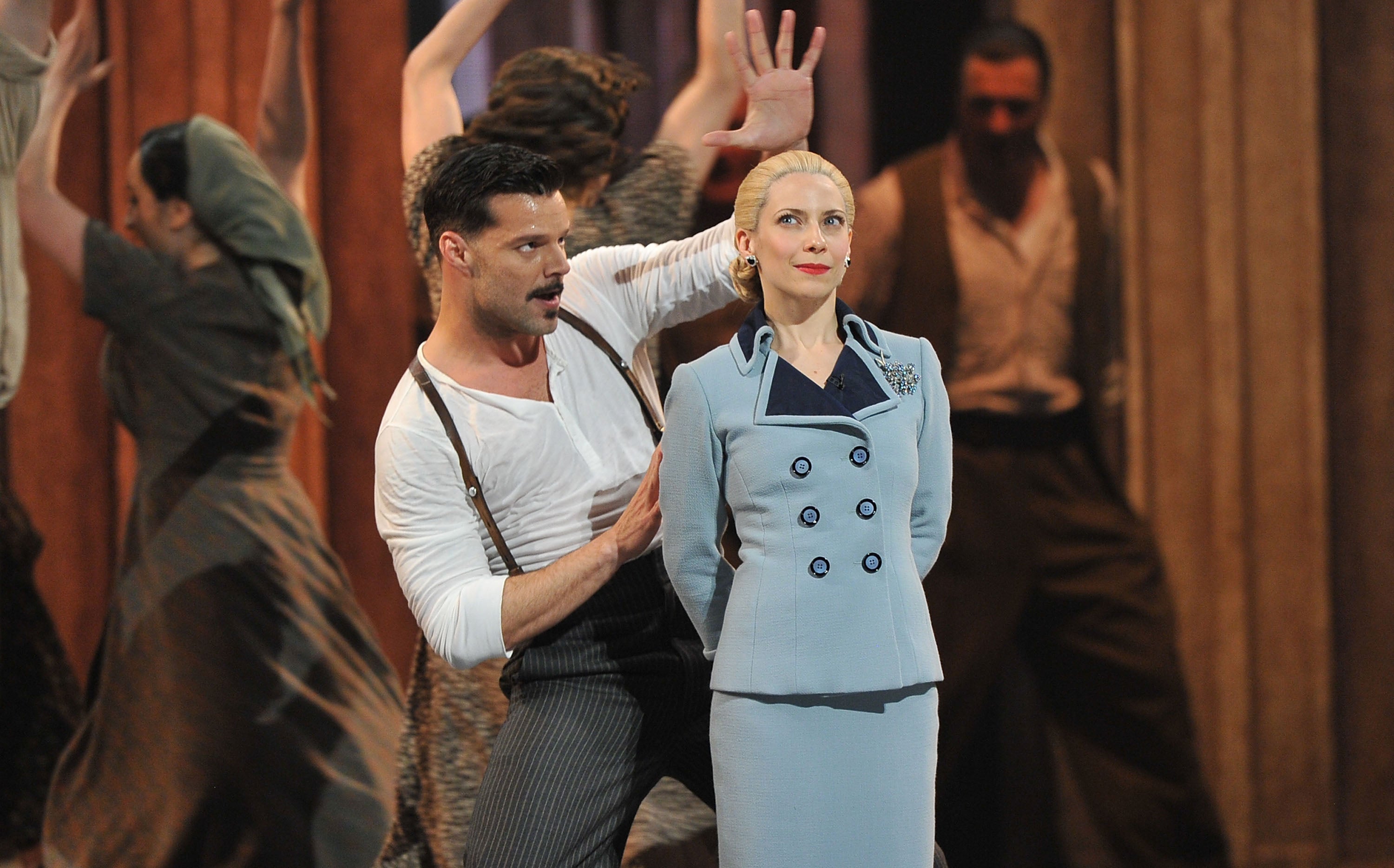

Most famous of all, though, of course, is the stage musical, Evita, by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber. This tells the story of Eva’s brief, brilliant but controversial life, which took her from nowheresville to the Casa Rosada presidential palace. It received a standing ovation on its opening night at London’s Prince Edward Theatre in 1978, with Elaine Paige starring – and ran for another 2,912 performances. A successful Broadway production followed.

Evita was adapted into a film starring Madonna in 1996, and is said by Donald Trump to be his favourite ever stage show. It returns to the West End this summer in a new production at the Palladium directed by theatre powerhouse Jamie Lloyd, with 24-year-old Rachel Zegler – star of the recent movie adaptation of Snow White and Hunger Games – in the title role.

How to explain, though, the world’s lasting fascination with the woman who was briefly married to the president of a Latin American country and who died in 1952? Clearly, a smash-hit musical helps maintain a subject’s fame over the years, but there is plenty about Eva’s story that attracted Rice and Lloyd Webber to her in the first place.

“She died so young, yet achieved so much,” says Jill Hedges, author of the 2020 biography Evita: The Life of Eva Perón. “She rose from nothing, to a position of immense wealth and power, yet never forgot where she came from.”

Maria Eva Duarte was born into poverty in 1919, in a small agricultural town called Los Toldos: one of five illegitimate children fathered by a farm manager (who died when Eva was a young girl) and a seamstress. Aged 15, she took off for the bright lights of Buenos Aires, intent on making it as an actor. And make it she did, finding success in a string of radio soap operas.

After becoming reasonably famous, she started a relationship with Colonel Juan Perón, then the labour secretary in Argentina’s military government. Perón was a widower aged almost 50 when he and Eva met; she was in her mid-twenties. The couple married roughly a year later, in October 1945, a few months before Perón was elected president.

Both were relatively low-born, and Eva in particular had an antipathy towards her country’s rich elite, which goes some way to explain the populist agenda that the Peróns pursued in power. Crucially, Eva wasn’t a spouse to disappear into the background. She was at the heart of policy, with Perón – aware of her mass appeal – happy to give her a platform. “I speak in the name of the humble [and] homeless, to cry out against the old evil days,” she declared.

Eva Perón was a little like Diana, Princess of Wales

Jill Hedges, author of the 2020 biography ‘Evita: The Life of Eva Perón’

For pretty much the first time in Argentina’s history, large sums were spent on building a social infrastructure for the poor: schools, hospitals, shelters and more. In many cases, Eva attended personally to those in need, handing out dentures to the toothless, for example, and medicines to the sick.

Her fame reached new heights. “A little like Diana, Princess of Wales, a few decades later, she showed incredible social sensitivity,” Hedges says, “and this resulted in a huge amount of public affection for her.” Her supporters called her Evita, a nickname that translates literally to “little Eva”.

Perón won re-election by a landslide in 1951. His wife turned down the chance of being his vice-president, though, in no small part because by then she was terminally ill. A year later, she would die and go on to receive a state funeral, with 3 million people lining the streets of Buenos Aires in mourning. Many of those people saw her as a saint who had been put on earth to protect them. The Vatican was inundated with requests for her canonisation. So influential was Eva’s legacy that when Perón was ousted from power years later in a 1955 coup, his usurpers had her embalmed body smuggled aboard a ship to Italy, and buried under a false name – so as to avoid its becoming a rallying point for the Peronist cause.

Another reason that her fame endures – and why it translates so well to the musical form – is that Eva’s life was a stunning case of rags to riches: an age-old story archetype in the vein of Cinderella, Aladdin, and Annie. In her case, those “riches” included diamonds and mink coats, which she was particularly fond of wearing.

For all the millions who idolised Eva, there were millions of others who loathed her. The latter mostly came from the wealthy classes, whom the Peróns taxed heavily and disempowered. They told their own tales about her, often misogynistic ones – that she was power-hungry, that she had slept her way to the top, and that much of the money meant for the poor was spent on her own wardrobe (hence the fabulous line from Evita: “They need to adore me, so Christian Dior me”). There were even rumours that she connived with her husband in the transfer of huge wealth from Nazi Germany to Argentina at the end of the Second World War.

With so many competing narratives, it’s all but impossible to get to know the real Eva – even for those embodying her. “She was a very polarising figure in Argentina – and still is,” says Elena Roger, an Argentinian actor who has played Evita in big productions on the West End and Broadway. “This made it both a challenge and a responsibility to portray her.”

As the writer VS Naipaul put it in a dispatch from Argentina for The New York Review of Books in 1972, “the truth begins to disappear; it’s not relevant to the legend”. The truth, of course, is never as interesting as a legend, and never survives as long.

Eva herself had been involved in conjuring a version of her own legend. On becoming Perón’s wife, she created what might be called a carefully edited version of her back story. She replaced her birth certificate, for instance, with a falsified document that concealed her illegitimacy, and destroyed all prints of the old movies in which she had played bit parts to erase any record of her as a struggling actor.

In Evita the musical, Rice presents his subject as a supreme social climber, keeping relationships with people only as long as they benefited her advancement; a hostile early biography of Eva by Mary Main called The Woman with the Whip is often cited as his chief source of information. Rice denies this, but did go so far as to describe his subject as “dishonest”, “fake” and “self-interested” (albeit also “fascinating”) in a podcast with the politics professor David Runciman.

Whoever you are, power brings out your true self… And the way Eva used her power, in such a brief and intense space of time, is fascinating

That view is far from the dominant one, though. After all the research that Hedges completed for her biography, the author came away with the belief that “Eva cared passionately about the causes she backed”.

There are at least two further reasons why Eva continues to enthral us. Firstly, she is at the centre of a great what-if of 20th-century politics. With her impassioned speeches made to the masses from the Casa Rosada balcony – and with the important role she played in granting suffrage to Argentinian women during Perón’s first term – Eva was, consciously or unconsciously, forging a presidential path. Had she not been cut down by cancer, she might have gone on to become the first democratically elected female head of state. That honour went instead to Sirimavo Bandaranaike, who became prime minister of Sri Lanka in 1960.

Secondly, her journey from entertainer to politician is one mirrored increasingly today. Eva’s successors in this regard include Ronald Reagan, Volodymyr Zelensky and, of course, the erstwhile presenter of The Apprentice who today occupies the White House. All found their performative skills to be transferable. (Trump says he saw Evita six times on its initial run on Broadway in 1979.)

It has been over a decade since Roger, now 50 years old, played Eva on Broadway, and still the actor finds herself in thrall to the role. “The musical character of Evita, just like the real Eva, was someone who assumed great power,” Roger says, “and for me that’s where much of the interest is. Partly because women in power [are so rare that] they’re always interesting, and partly because, whoever you are, power brings out your true self. Once you have it, you no longer need to pretend to be somebody you’re not. And the way Eva used her power, in such a brief and intense space of time, is fascinating.”

Certainly, from the ongoing stream of books and films and musical revivals, it’s clear Roger is not alone in her fascination. Eva Perón’s final words reportedly were Eva se va: “Eva is leaving now”. The truth is, she has never left us.

‘Evita’ runs at the London Palladium from 14 June to 6 September; evitathemusical.com