It was the world’s largest invasion force ever assembled. But when they marched on Russia, French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s “Grande Armee“ was doomed to failure and death, and not just on the battlefield.

Now, a French research team has uncovered two new culprits that contributed to the annihilation of the 500,000-strong army during the 1812 Russian campaign.

The killers? Two species of bacteria, responsible for causing fever.

It’s a surprise finding by a French research paleogenomic group led by scientists at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France.

Typhus and trench fever were previously established as diseases that tore through the ranks of Napoleon’s army during the 1812 retreat. The newly uncovered infections cause different diseases with similar symptoms.

“Even today, it would be nearly impossible to make a differential diagnosis between these [fever] symptoms with the different pathogens,” said Nicolas Rascovan, a paleogenomicist from the Pasteur Institute, who led the study.

“It would be impossible for a doctor to tell you which pathogen is infecting you.”

First retreat, then death

Seeking to force Russian Tsar Alexander I to comply with his trade embargo against Britain, Napoleon led the largest army Europe had ever seen across Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus before marching on Russia.

In the summer of 1812, his forces successfully captured Moscow. From there, they fell into a stalemate with those of the Tsar, who refused to negotiate.

Laden with treasure, and Napoleon himself having already departed for Paris, the Grande Armee delayed its withdrawal until October 17.

It was then that a new threat advanced. Rather than Russian soldiers, the Grande Armee now had to contend with the triple threat of the advancing Russian winter, diminishing rations and disease. Barely 30,000 soldiers, around 6% of the original force, are recorded as having survived the withdrawal.

As well as starvation and the freezing weather, typhus — a common infection among army camps of the era — was thought to be one the deadliest hazards that haunted the Grande Armee.

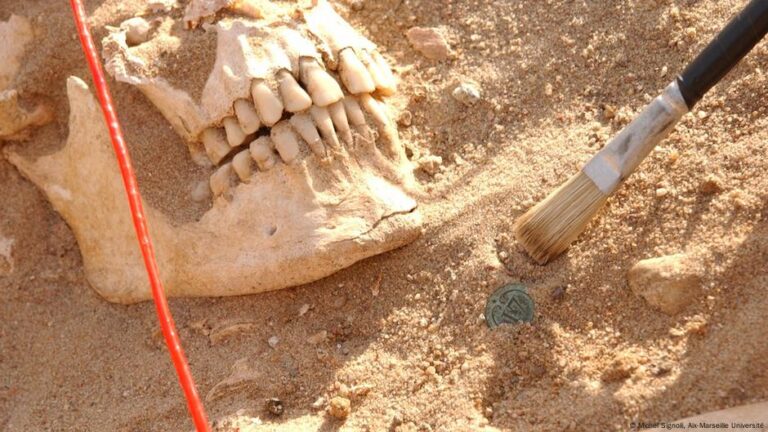

Then, in 2002, excavators unearthed the bodies of hundreds of Napoleon’s soldiers in Vilnius, theLithuanian capital, one of the army’s key stopping points. A 2006 analysis of some of these bodies found genetic evidence for Rickettsia prowazekii, the bacteria that causes the expected typhus, and Artonella quintana, which causes trench fever.

But a new analysis of 13 different bodies from the Vilnius mass grave has uncovered new killers.

Modern DNA testing unearths deadly bacteria in ancient remains

Rascovan’s team went searching for typhus and trench fever, but found two different diseases instead.

Using modern techniques for analyzing ancient DNA, the researchers found genetic remains of the paratyphoid-causing Salmonella enterica enterica bacteria, and Borrelia recurrentis, the cause of relapsing fever.

The four diseases identified in the remains of Napoleon’s troops all carry similar symptoms associated with fevers, such as muscle aches and fatigue. To army medics in 1812, they would appear to be the same affliction. When combined with food shortages, freezing conditions and the fatigue of battle, these fevers would have made survival almost impossible.

Rascovan expects more deadly diseases could still be discovered among the dead.

“Ancient DNA has moved forward as a field [since 2006], has expanded enormously,” Rascovan told DW.

“We can, today, 200 years after, do a diagnosis and find all the different pathogens that were potentially present.”

Paleogenomics answers mysteries from the past

Paleogenomic scientists analyze ancient remains for genetic markers. The findings can often be surprising.

Earlier this year, Rascovan’s team found that atype of leprosy was already circulating in the Americas prior to the first European arrivals in 1492.

The discipline has also been used to chart the movement of the bubonic plague out of Central Asia during the Bronze Age. And researchers have tracked the movement of human groups around the world as well as how they interbred with each other.

It’s even been used to shed light on the illnesses that plagued German composer Ludwig van Beethoven.

Historians are excited about the possibilities of using DNA analysis to improve understanding of major events in recent centuries.

“Not only because it makes our historical knowledge a little bit more precise, but it also gives us an insight into different kinds of social conditions,” said Erica Charters, a historian of war and disease based at Oxford University in the UK.

Charters, who was not involved in Rascovan’s study, said the scale of Napoleon’s conquests by 1812 would enable disease to move easily across Europe—not just because of the movement of his soldiers, but also due to trade among the French Empire and its neighboring alliances. One of the bacteria uncovered by Rascovan’s team was even found to have English origins. Given Britain was Napoleon’s primary enemy, and separated from France by an ocean, it shows how mobile diseases could be in times of major conflict.

“The retreat from Russia for the French Army is astounding,” Charters told DW. “They’re losing 95% of their forces from deaths and there’s very few battles.”

Disease and war come together

From a historical perspective, these kinds of numbers are somewhat unusual, Charters said. But high rates of disease, and death from disease, are not at all unusual during wartime.

The breakdown of civil infrastructure and the loss of food supplies for communities and militaries increase outbreaks of disease, she added.

“We actually see a lot of epidemics rising when there’s an outbreak of war,” she said, “These tend to be phenomena that break out together.”

She points to an outbreak of syphilis in Europe amid conflicts in the 15th and 16th centuries, and the spread of influenza following World War I.

Understanding how diseases spread during war can also give an insight into the risks associated with modern conflicts: sanitation, not simply advances in medicine, is a critical factor.

“If you look around today and you look to see where epidemics may be happening, it’s very often because there’s been conflict which has broken down water supplies, Charters said, “which means that sanitation is gone and now means you have outbreaks.”

Edited by: Kristie Pladson