CLEARWATER, Fla. — When Charlie Manuel started talking again, he was speechless. It had been five days since his stroke. He felt better. Over time, he will regain feeling on his right side. But last September, there was no news.

“I knew what I wanted to say,” Manuel said months later. “It does move you. You know what to say, but you can’t say it.”

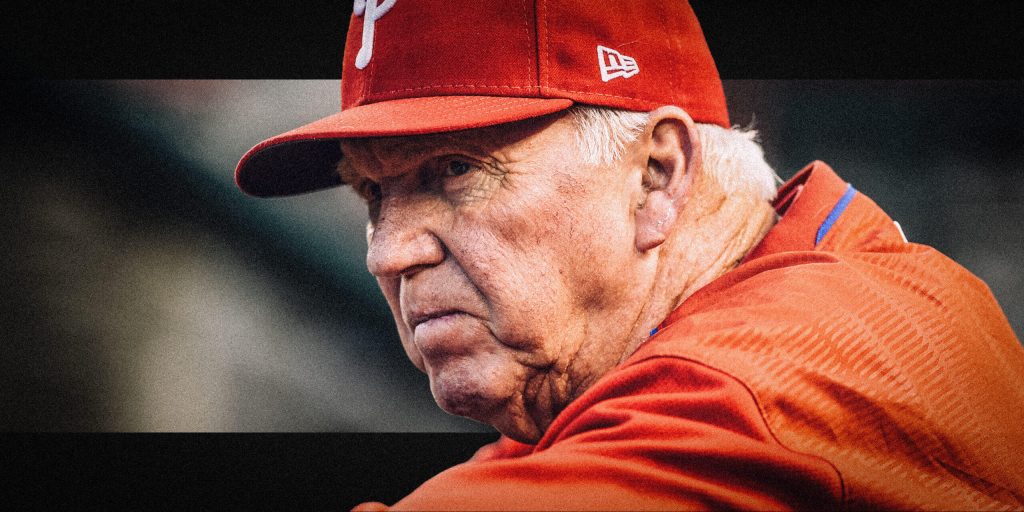

Manuel is the ultimate baseball figure, having been involved in the game for over 60 years. Known for his love of hitting, signature mistakes and colorful language, the winningest manager in Phillies history was always most at home behind the batting cage. The Phillies fired him as head coach in 2013, and five months later they hired him as a front-office consultant. He hasn’t left yet. The role is now largely ceremonial, but Manuel never saw it that way. “On one hand, I’m real,” Manuel said. “I’m honest.” He’s been consistent in spring training. For 80 years he suffered from health problems, in and out of hell. This is different.

The stroke damaged a specific part of his brain that controls speech; doctors diagnosed Manuel with expressive aphasia and dysarthria. It was the most depressed and depressed his wife, Missy, had ever seen him. He existed to talk and hit people, and now, he couldn’t speak a complete sentence. He doesn’t want visitors. He doesn’t know how to make phone calls.

“Sixty-one years in baseball, this is how I’m going to go out,” Charlie told his wife.

“You can’t go anywhere yet,” Missy said.

Lakeland Regional Health’s critical care team intervened during a routine cardiac catheterization on Sept. 16. They had to act fast: Manuel had suffered a stroke. “It looks like a TV show,” Missy said. “And I was just running, trying to keep up with them.” Charlie woke up. He squeezed Missy’s hand.

Surgeons inserted a stent into Manuel’s heart; a 45-minute surgery followed to remove the blood clot that had caused the stroke. Doctors hope he will recover, but they are unsure how much damage the stroke caused. “Time is brain,” they kept telling Missy. The Phillies released a 62-word statement asking for “thoughts and prayers at this time.”

Missy was both scared and optimistic.

So she turned on the Phillies game on her iPad in Charlie’s hospital room. Days turned into weeks. Doctors tested his cognitive abilities. Missy told them that if they had any questions, they should come over when the Phillies played. It may not always sound like Charlie, but he’s there.

“He’s second-guessing it,” Missy said. “You know, he’s an armchair manager. He’s destroying pitchers, batters.”

The Phillies went on to win. Manuel was released from the hospital during the National League Championship Series. He returned home to Winter Haven, Florida, to watch the Phillies lose Games 6 and 7.

He was disappointed, but worse, there were no words. The magnitude of the challenge he faced shocked him.

“I can’t curse,” Manuel said.

The twist is beautiful and something Manuel can appreciate. His approachable demeanor became the topic of daily roasting on 94.1 WIP during his time coaching the Phillies — both before and after the World Series championship. But he has become a legend in Philadelphia, a status reserved for few in the city.

He was a .198 hitter in the major leagues, but his country accent and prodigious home runs made him a folk hero among Japanese players. He was the whisperer of Cleveland’s great offense but came to the Phillies as an outsider. He became an easy target for upset fans before winning five straight division titles from 2007-11. The Phillies haven’t won a game since, and time is good for Manuel’s legacy. Now, strangers are obligated to shout “Cholly!” when they see him. And, in the days after Manuel’s stroke, sports talk radio invited callers to leave messages of support. WIP sent three large audio files to Missy. She played these songs to Charlie while they were in the hospital.

He smiled.

“I think it helped him a lot,” Missy said. “Encouragement from people all over the world. Phillies fans everywhere. A lot of them have had strokes. Lots of speech therapists and occupational therapists. I just play them.”

But for the first month, Manuel didn’t answer the phone. He was frustrated. He didn’t sound like what he was supposed to say. “Sometimes I don’t speak at all,” Manuel said. “I just went into my room and sat down.” Missy nudged him. One of the few people Charlie trusted, his old pitching coach Rich Dubee, drove 90 minutes to be with him. Doobie could feel his worry.

“You could tell by the way he spoke and acted that he realized that sometimes he didn’t say things right,” Dube said. “He did realize that.”

Three months after his stroke, Manuel remains alert. In December, he began to emerge from the darkness. Missy took him to visit some grandchildren at the circus in Sarasota, Florida, and some Phillies fans recognized Manuel. He always invited people into his orbit. That’s why he achieved mythical status in Philadelphia. That’s why people feel the need to approach him.

At the circus, he took some photos.

“Did they know you had a stroke?” Missy asked.

“No,” he said. “I didn’t talk to them long enough.”

But she saw new confidence. Manuel’s speech was very unnatural.

“I mean, it’s natural,” Manuel said. “I’m not sad or anything. But what are we going to do?

Charlie Manuel and one of his grandsons have been playing professional baseball since 1963. (Courtesy of the Manuel Family)

In October, he completed his first speech therapy session and was hopeful. “It’s been a pleasure talking to you,” Manuel said to Pam Smith. “I think it’s going to help.” Smith, a speech therapist at Winter Haven Hospital, said Manuel has a gentle, quiet demeanor. Sometimes, practicing word retrieval becomes boring. Charlie was frustrated. But whenever he talks about his interests, his attitude changes.

“So,” Smith said, “one day I pulled out some baseball trivia. Now the tickets are here.”

Most stroke patients don’t fully return to their previous condition, Smith said. There will be remaining flaws in Manuel’s speech. That made Manuel joke – and that’s a good thing for him. Speech problem? That’s how I talk all the time! He had never been a lover of grammar. He often says the wrong thing in management. He was angry that some people confused his sloppy communication skills with a lack of intelligence. He has his style and it’s evident.

He wants it back.

“I was walking really fast,” Manuel told his therapist, “but I can’t remember the words.”

They made some small progress. They started to enjoy it. One day they were studying his writing. This is also affected by stroke. “We strayed away from what we really wanted to write because Manuel wanted to be able to sign his name,” Smith said. “He wanted to be able to sign baseball cards.” He practiced his signature over and over again. Manuel is most astute when talking about hitting. Smith is his newest student.

Search for words like basic hit #strokesurvivor pic.twitter.com/uXrkGZY9VD

— Charlie Manuel (@CMBaseball41) November 29, 2023

Motivation is a powerful aid.

“It’s a therapeutic technique,” Smith says, “which is to engage someone in something they enjoy.”

Back in October, Phillies marketing staff did their part, planning to have Manuel play in the World Series if the Phillies were able to attend. If he were on the field for his first pitch six weeks after his stroke, the entire stadium would go crazy.

Missy liked the idea. It can energize a depressed Charlie. It’s nice to have goals. He wasn’t too enthusiastic about it. He won’t be able to throw a baseball. He was frightened by the thought of all the people trying to talk to him.

Two months later, Manuel was smiling. “Ah, I don’t know,” he said.

The goals are different now. Manuel still has a seat in the team’s front office. His official title is Senior Advisor to the General Manager. That requires scouting out some amateur players and playing in minor league games to get a feel for the Phillies farm system. Manuel was determined to keep going.

“I can go fishing wherever I want,” Manuel said. “I can play golf all I want. But at the end of the day, I still love watching baseball.”

Now he still stutters when he speaks. He would miss a word. He pauses when he runs out of words. He would mumble the wrong words. He doesn’t always sound like he used to because the muscles he uses to speak are weakened by the stroke. But some stroke patients suffer from aphasia and are unable to speak at all. His brain is solving some puzzles.

“He’s getting back to who Chuck was,” Doobie said.

I am so proud of these fun, interesting and dedicated therapists @LKLDRegional Banash Academy is my coach! They get me up and moving every day. I’m happy to be home, but I’m going to miss all my new friends. I am grateful and grateful to all the medical staff here who helped me recover from my stroke❤️❤️❤️💪🏻 pic.twitter.com/2yg5BUMHnS

— Charlie Manuel (@CMBaseball41) October 6, 2023

Manuel did something last month that reassured Missy. He was in that tone again. He was engrossed in someone’s swing. He knows how to heal it. (The player wasn’t with the Phillies, so Manuel preferred to keep it a secret.) For days, that was all he talked about. Missy loved it.

Then Manuel startled his therapist, Smith. “I’ve got to get better at talking through spring training,” he said.

That’s the goal.

“Yes, I want to go,” Manuel said. “If the Phillies want me to come to spring training, I’m going to come to spring training … (but) just because I want to come doesn’t mean I can come. I’m going to do what I have to do.”

During a recent therapy session with Smith, he shared a secret. Manuel wrote something a long time ago. He reads it often.

“You wrote a poem?” Smith said.

Manuel did it with some help. That started in the early 1970s, when he was a backup with the Minnesota Twins. He called it “my most unforgettable day.” Among them, “Some redneck hit .182” for his idol Harmon Killebrew. Manuel faced Jim Palmer and he hit a home run.

The roar from the stands unleashed a deafening scream…

Then Charlie fell off the bed and it was just a dream.

He has been reciting these words for decades. He felt bad because he had to read a piece of paper to Smith. He became agitated and had difficulty expressing himself verbally. Smith didn’t interrupt. “What he wanted to say was right,” Smith said. He moved on.

“I just thought it was the coolest thing I’d ever heard,” Smith said. “The funny thing is, yeah, he just gets happy when he talks about baseball. He has a twinkle in his eye.”

He monitors his heart rate. He walked three miles through the neighborhood. He can curse again. He wants to get back to bench pressing.

“The truth is,” Manuel said, “I wanted to do it just to see if I could do it.”

“That’s what it’s all about,” Missy said. “A lot of times, he does it to prove to himself that he can do it.”

Charlie glanced at Missy.

“I’ll tell you this: I’m going to be in baseball forever,” Manuel said. “I will always be in baseball.”

Manuel turned 80 on Thursday. “I don’t want to have a party,” he said. “My life is a party. I don’t throw parties. My life is a party.” There are other things.

Pitchers and catchers will report within 43 days.

(Above: Eamonn Dalton / Competitor; Photo: Mitchell Layton/Getty Images)