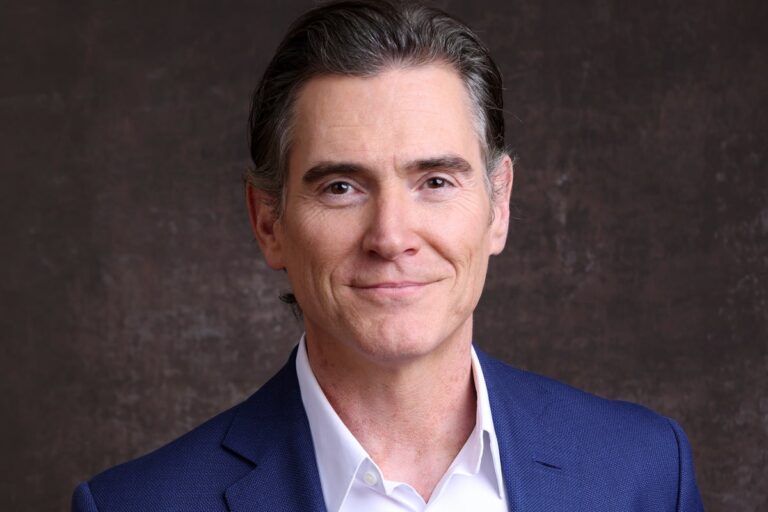

Billy Crudup is in an echoey east London rehearsal room, practically vibrating as he unpicks one of the best scenes in one of the year’s best films. The star of Almost Famous and The Morning Show, dressed in a grey quarter-zip fleece, looks faintly horrified by his own enthusiasm. “It’s the nerdiest job I’ve ever had,” he says, eyes lighting up.

In Jay Kelly, Noah Baumbach’s Fellini-like meditation on ageing and Hollywood vanity, Crudup plays Timothy, a former drama-school classmate of George Clooney’s fading movie star of the title. Though clearly the more talented of the pair, Timothy didn’t “make it” as an actor, and became a child therapist instead.

The pivotal scene happens in a bar. Jay, in town for his mentor’s funeral, urges his old buddy to show off his Method genius there and then by reading the menu in character. Timothy takes a breath and steadies himself; soon, tears are cascading down his face to the words “truffle parmesan fries”. It’s hilarious – yet there’s a lot more going on. From across the table, Jay watches, mesmerised, as years of unspoken rivalry bubble to the surface.

The twist is that Crudup really did have to use Method acting techniques to get those tears out. The double twist is that this 57-year-old has never been a fan of Method acting.

For Crudup, whose approach is based on spontaneity and collaboration, the real issue isn’t so much the technique as its effect on others. He’s less damning than Brian Cox, who called it “f***ing annoying”. But, he explains, if a director needs to give a note mid-scene – move left, say – and the actor insists on remaining in character, there’s a problem. “You can’t just say, ‘Sorry, Daniel [Day-Lewis], can you step outside of that for one second?’ To the other actors and crew, it feels selfish.”

Not that directors are immune to antisocial techniques – he mentions William Friedkin unexpectedly firing a gun on the set of The Exorcist to provoke an expression of shock in an actor. “Let me tell you, it’s a great f***ing moment,” says Crudup. “But would I say that gunfire on a set is the best way to provoke a response? Generally speaking, no, that’s a bad idea… I used to get in disagreements with directors and other actors because I didn’t want to be tricked into anything,” he adds.

Yet the script for Jay Kelly required crying, so he did what he’d never done before: applied the nuts and bolts of “the Method”, excavating a painful memory, working through the five senses, picking at the scab until something gave. “It turns out re-traumatising yourself works,” he says. Before filming, he’d told Baumbach and Clooney he didn’t know if it would. “Feelings, for me, emotions, for me, they’re capricious,” Crudup explains. Yet it worked so well, in fact, that despite only being in the film for 10 minutes, he is now expected to feature heavily in the Oscars conversation.

Crudup speaks slowly, carefully; his face buffers – eyes closing, eyebrows dancing independently – as if he’s rifling through his brain’s archives. The very idea of him playing an actor tickled him. “I’m already as actory as they get,” he says, laughing. “It’s like nerd-on-nerd crime.”

Ever since his film debut opposite Robert De Niro and Dustin Hoffman in 1996’s Sleepers, Crudup has made a career of men you can’t quite figure out. He’s been a duplicitous CIA agent in The Good Shepherd, a stone-faced space captain in Alien: Covenant, a calculating attorney in Spotlight, and a serpentine network executive in The Morning Show. There’s even a degree of detachment to his soft-spoken handyman in 20th Century Women. Call Crudup a connoisseur of the inscrutable. He’s drawn, he says, to “unusual” characters he doesn’t “fully understand. Part of that is because I’ve been afforded the opportunity to learn about people and learn about humanity in this stupid job I have,” he explains. “I want to know how a human being who acts like that, and maybe thinks like that, manages the world.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

For someone who has quietly, doggedly assembled such an impressive body of work, Crudup is surprisingly self-critical, dismissing a lot of his early film performances as “not authentic”. Even Almost Famous, Cameron Crowe’s beloved coming-of-age classic, doesn’t escape his scrutiny: “I can pick out moments where I go, ‘That’s totally false.’” The closest he’s ever come to self-satisfaction, he says, is playing all 19 characters in the one-man play Harry Clarke, in 2017, at New York’s Vineyard Theatre, where he was “in control of the text” and “wasn’t self-conscious”.

The stage, one senses, is where Crudup is happiest. We meet a few weeks before his new play, High Noon, gets its world premiere at the Harold Pinter Theatre in the West End. Adapted from the 1952 film by Eric Roth, who wrote Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) and won a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for Forrest Gump (1994), it casts Crudup as yet another man who is hard to read.

You can’t have government officials systematically disobeying laws with no accountability

He’s Will Kane, a retiring marshal counting down the minutes before he confronts a pardoned killer who is returning to take revenge. The role of this towering, taciturn lawman was made famous by Gary Cooper and isn’t an obvious fit for Crudup, he admits. But Roth’s adaptation, which unfolds in real time and uses a ticking clock to ratchet up the tension, offers something more complex than the original film’s stoic masculinity. Here, the love story between Kane and his Quaker wife Amy (Denise Gough, whom Crudup praises as “an acting animal”) is deepened, forcing Kane to articulate what the film kept buttoned up. “The film was not really even about courage,” Crudup says. “What it’s about is cowardice.”

Kane has protected the town for 17 years, but when the murderous outlaw returns, everyone scarpers. In the play, Crudup notes, the interpersonal pressure matches the civic kind. Kane and Amy “have never had a love like the love they have for one another”, but his decision to fight breaks their marriage vows, after he promised to give up his guns. This conundrum – the choice between duty and devotion – lends the play urgency for 2025. “There’s that percolating in masculinity right now,” Crudup says. “How do I exist as a man in the way that I kind of inherited… and then we had a cultural revelation, that we can’t have systems in place that oppress certain groups of people.”

The resonance with America’s political situation is unmistakeable. “We’re wrestling right now with how to create civility in what is becoming an increasingly lawless community,” he says. “You can’t have government officials systematically disobeying laws with no accountability from Congress, and no application of force by the Supreme Court, and it not be somewhat lawless.” Kane himself is morally dubious – “He’s a bully,” says Crudup, “but he’s a bully for the law.”

Crudup, the middle sibling of three brothers, had a peripatetic childhood, moving from New York State to Texas and then to Florida. After his parents divorced each other for the first time when he was young, he lived with his mother, who worked in advertising for local political parties in Dallas. His father was a different sort: bookie, loan shark, salesman, a real wheeler-dealer who would often buy products from warehouses and try flogging them again, convinced his charisma could shift anything.

The result of having such an eccentric dad was that Crudup wanted some semblance of stability for himself. So naturally, he chose acting. Luckily, he has his father’s resourcefulness and charm. Crudup is today upbeat and voluble; a single answer can run to six minutes. He’s modest, too. Some of his best roles, he says, have been when he wasn’t the director’s first choice. Take Russell Hammond, the enigmatic guitarist in Almost Famous. The part was originally going to Brad Pitt before Pitt dropped out. When I bring up that film, Crudup tells me a story he still can’t quite believe happened. Walking through LAX, he spotted a tall figure with a leonine mane of hair. “Oh my God, that’s Robert Plant,” he thought.

As Hammond, Crudup delivers one of cinema’s most iconic rockstar moments, declaring “I’m a golden god!” from a rooftop. Crowe had told him it was originally Plant’s line. “My dedication to Zeppelin began during Almost Famous, and it hasn’t stopped,” Crudup tells me. But paralysis struck. Plant vanished before he could approach. Then Crudup discovered the musician sitting just behind him in first class.

Five agonising hours passed. Nothing. Then, as they disembarked, Plant turned to critique Crudup’s battered luggage. Seizing his moment, Crudup blurted out his connection to the film, and that famous line. He puts on an English accent for my benefit. “Oh, it is you,” Plant replied. “You stole my line.” “My line now,” Crudup recalls saying. The flight attendant sealed the moment: “The two golden gods.”

“Best day ever,” Crudup says now, arms astretch.

Another role for which Crudup wasn’t first choice was Dr Manhattan in Watchmen, Zack Snyder’s unhinged 2009 adaptation of Alan Moore’s unremittingly dark superhero comic book. In a film that has grown in reputation in the years since, Crudup is the glowing blue colossus with godlike powers – a role Keanu Reeves was initially down to play. “When I read it, I couldn’t believe it,” Crudup recalls. “This was around the emergence of Iron Man, so there was a new kind of attachment to the commercialisation of superhero figures.”

The script questioned that iconography. “What Alan Moore was saying was, ‘You want me to show you who dresses up in costumes? Psychopaths, sycophants, freaks. There’s no good superhero coming in who’s wearing a mask.’” And if someone had genuine superpowers, Crudup notes, “they wouldn’t care for humanity. They’d go off to Mars and contemplate the universe. I thought, ‘F*** yes, that’s so subversive.’” He called his graphic-novel-obsessed younger brother to discuss the role. “F*** you,” his brother replied, furiously jealous when he heard it was Dr Manhattan. “I was like, ‘OK, got to go. I’m doing it.’”

Crudup had a similar reaction when he saw the script for The Morning Show, the drama series set in the world of breakfast TV news and co-starring Jennifer Aniston and Reese Witherspoon. “To me, it read like [the 1987 film] Broadcast News and [Paddy Chayefsky’s 1976 satire] Network,” he says. While the glossier aspect of the show “wasn’t exactly what I was picturing”, The Morning Show has been good to him. As Cory Ellison, the president of a TV news network, he has won two Emmys. Besides, he adds, “I go where I have to go, where the work is. I can’t generate any material.” He elaborates: “I tried to write something a while ago, and it was just f***ing repugnant.”

Before The Morning Show, Crudup was rarely stopped in the street. It was only when he was out with his wife, the Oscar-nominated actor Naomi Watts, whom he married in 2023, that people would come up to him. “And I would take the picture of them and Naomi,” he laughs. All of a sudden, though, people are now asking him for selfies, such has been the popularity of The Morning Show (which begins filming its fifth season after he finishes High Noon).

I ask Crudup how he feels about fame. “Jimmy Carter, the former president of the United States, gave this speech in the Seventies that people hated,” he says. “And it was kind of a ‘Come to Jesus’ sort of thing with America and its conscience, saying, ‘If you guys keep going after obtaining things, you’re going to forget what the purpose of living is.’” He smiles. “That’s how I feel about fame.”

‘Jay Kelly’ is on Netflix now. ‘High Noon’ is at the Harold Pinter Theatre from 17 December until 7 March. Tickets can be bought here