US sprinter Michael Johnson spent his career breaking records, but even at his peak he realized track and field was broken. Now, with his new venture Grand Slam Track, the 57-year-old is determined to fix it.

Despite producing global superstars and spectacular performances, athletics struggles to maintain visibility and financial security outside of the Olympics.

While Johnson’s Olympic triumphs made him a household name every four years, he knew the sport’s visibility outside the Games was vanishing.

“I spent a better part of my career dominating my events, being the fastest in the world, and having to explain to people that I was still racing,” Johnson told DW. “My value as an athlete suffered because it was tied to one major event every four years.”

The system, during Johnson’s career in the 90s and to the current day, rewarded brief moments of glory but offered little support for building lasting careers.

Grand Slam Track is Johnson’s answer: A bold new series that is designed to showcase athletes year-round and reignite fan passion beyond the Olympic spotlight.

“When you have a situation where the athletes are suffering and the fans are suffering — and you can fix it — you should fix it,” he said.

Fight for relevance

While Johnson himself carved out a successful post-sports life, notably working in broadcasting, his motivation to create Grand Slam Track was rooted in a deep frustration with the sport’s missed potential.

Over time, Johnson has watched the gap between track and other major sports widen. It wasn’t a question of talent but of structure.

He saw the need for a system that gave athletes regular, meaningful exposure and fair rewards for their performances, not just a spotlight every four years.

“We have athletes… who literally are taking on jobs at Walmart and suffering financially,” Johnson said. “Then they look across to their counterparts in other sports and see someone signing a five-year, $100 million contract — and they wonder why not me?”

“These are the best in the world, yet they are suffering financially. Meanwhile, fans who want to watch more track and field outside the Olympics often can’t find it.”

Innovation key to attracting athletes and audiences

The new competition has been built to close the gap, bringing innovation to the traditional athletics meet, allowing top names to compete against each other more often.

Each athlete competes in two races at every meet, their primary event and a secondary event that complements it.

Athletes are divided into two groups: Racers, who compete across the full series for the Grand Slam title and earn a base salary, and challengers, who rotate in and out of individual meets to push the racers.

Points are awarded at each event based on performance, with rankings carrying across all four meets to determine the overall Grand Slam champions who win $100,000 (€87,725) in prize money.

“We wanted to innovate and modernize,” Johnson said. “But also stay true to the sport and honor its culture.”

The first meet took place in April in Kingston, Jamaica, and will be followed by events in Miami (May 2-4), Philadelphia (May 30 – June 1) and Los Angeles (June 27-29) in the United States. Unlike existing events, such as the Diamond League, the new track and field league focuses heavily on rivalries, narratives, and direct competition.

“Athletes want to compete against each other more often, but there has to be an upside for them,” Johnson explained. “We’ve created that upside — fair compensation, visibility, and brand-building opportunities.”

A new generation embraces the concept

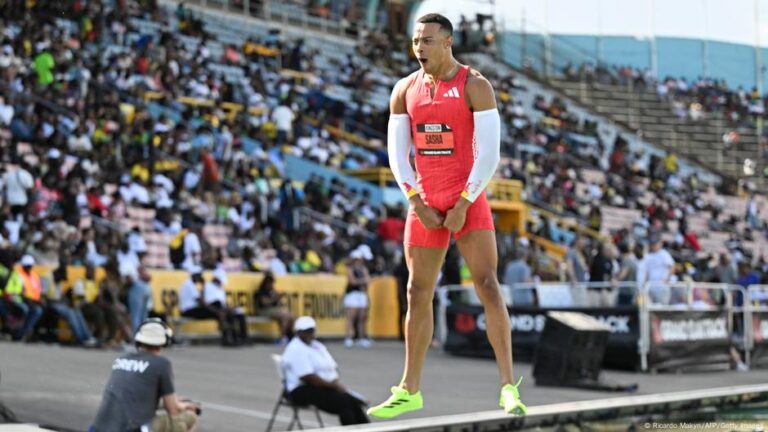

French hurdler Sasha Zhoya represents the new generation of athletes ready to seize this opportunity. Still only 22, he saw Grand Slam Track as a natural fit for his ambitions the moment a post came up on his Instagram feed.

Zhoya, whose athletic background includes not just hurdles but also sprints and pole vault, immediately recognized the value in a format that rewarded versatility and showmanship.

“The concept behind it, where athletes have to double up on their main event and a secondary event, I thought that was really cool,” Zhoya told DW. “It’s an opportunity for me to go back to my sprinting roots. I was vibing with that from the start.”

Although at the start of his career, Zhoya is already aware of the realities facing track athletes, both financially and in terms of reaching younger audiences.

“Track and field haven’t been a show for a long time,” Zhoya said. “The Grand Slam is really working on making it a show again, making it more appealing for the younger public. If we can have hype outside of just the Olympics, that’s what everyone wants.”

A slow start but building toward a sustainable future

Michael Johnson knows launching a new league comes with challenges. Sprinting superstar Noah Lyles skipped the opening meet in Kingston, signaling he’s not yet sold on the idea. Speaking on the “Beyond the Records” podcast, Lyles said he was critical of it because he felt it was the closest thing athletes have had to professionalism. He wants stronger city partnerships, and better storytelling, among other things.

Attendance in Kingston was sparse, and some athletes were critical of excessive downtime and lackluster TV coverage. Johnson is aware of that but also wants to grow slowly, with the four-time Olympic Gold medallist comparing the league to the training process that led him to success: persistence, adjustment, and long-term focus. Still, both Johnson and the athletes involved share a clear belief: Grand Slam Track isn’t just a new league, it’s an essential evolution.

“We’ve had one competition,” Johnson said. “It’s just the beginning. You don’t realize your potential in your first race. If there’s ever been a group of athletes that could carry the future of the sport forward, it’s this group.”

Edited by: Jonathan Harding